The artist, Charles Grey, painted this vivid portrait of Alexander Chesney in 1841. Grey painted with an intense sense of realism and he pays close consideration to every mark of age on Chesney’s worn face. At the time of the painting, Chesney would have been around eighty-six years of age. Grey portrays Chesney seated at a table with a legal document in his hand and a well-worn family Bible at his side. Grey chose to depict Chesney with the possible appearance of astuteness and in the act of intellectual inquest. Despite his advanced years, on his face is a resolute look of determination and, perhaps, a hint of sorrow.

Prevailing Historical Misconceptions

When initially attempting to examine the subject of Loyalism during the War of American Independence, one discovers that there is a real dearth of information within the public sphere concerning this topic when compared to the multitude of texts that address other aspects of the conflict. Indeed, historians on both sides of the Atlantic have generally neglected to account for the critical components of American Loyalism during the War for American Independence. Such negligence is somewhat pardonable when one considers that Loyalism is a complex topic that is most challenging to define in general terms. Noted British historian, Piers Mackesy reflected on the state of the surviving Loyalist documents and personal writings concerning the war and found that they were “a nightmare world: a world of insubstantial fears, jealousies, and plots.”[1] With this in mind, it seems that Loyalists have for too long lingered in the margins of the conventional histories of the conflict. These persons were the ones that lost the war, which labels them as regressive and objectionable for supporting what was perceived to be an erroneous cause that ultimately ended in utter defeat. It is that type of narrow thinking by many previous scholars that have ensured that Loyalists will continue to inhabit the margins of our historical understanding of the period.

Accordingly, a continuous reassessment is required given the individual nature of Loyalism. Pursuant of that end, W.W. Abbot observed that “[l]oyalism in the American Revolution begins with the problem of motivation – why certain Americans remained loyal to Britain.”[2] In order to push forward the boundaries of our understanding of this intricate topic of Loyalist motivation, we shall engage in an in depth examination of the life of Alexander Chesney and analysing the four essential local determinants: extent of social integration, religious affiliation, bonds of patronage and familial ties, and personal interest, the author intends to draw attention to common factors that seem to have influenced individuals that were similar to Alexander Chesney. Ultimately, by investigating these multidimensional aspects, one ought to be able to glean insights into the individual thought process that facilitated an individual’s decision to take up arms against their fellow countrymen and to remain a King’s Friend. When one first commences an examination of the circumstances surrounding the development of Loyalist narratives, one tends to find broad descriptions that are generally accepted as the archetype for every individual loyalist. However, when historians developed that model, essential pieces of the narrative begin to fall away from the main body. These critical portions then become part of an undercurrent that is frequently relegated to an unnoticed footnote within our nation’s history, if recognized at all. Moreover, we often fail to understand that these broad assertions are merely imagined individuals that inevitably exclude certain portions of the population that did not fit into the narrative.

To illustrate this point, the author would like the reader to think about the conventional narratives of the American War of Independence. American textbooks relay accounts that conjure up images of Washington, shrouded in darkness, standing at the head of a bateau crossing the Delaware River teaming with ice as an impenetrable snowstorm raged in order to attack drunken Hessians at Trenton. Next one envisions open fields dense with smoke, and the crack of musketry erupts shattering the low roar of the desperate struggle, while lines of untested, blue-coated Continental soldiers clash gallantly against columns of grim-faced British regulars in their faded redcoats. The narrative then shifts to desperate and ragged Continentals huddled around woefully pitiful campfires eating boiled leather at Valley Forge as the icy grip of winter relentlessly harasses the demoralised army, while a rough Prussian shouts out the manual of arms in French. Finally, the storyline swiftly concludes with Washington’s spirited defeat of General Cornwallis at Yorktown, which seemingly ends the war and grants the United States their hard-won independence from Great Britain.

Now that one has those famous images of the war in your mind’s eye, the author wants the reader to partially banish from their mind’s portions of those visualizations because they are only popular imaginings brought about by the perpetuation of broad narratives about the course of the war. While these images do contain elements of truth, they are merely popular conceptions of the conflict, yet these images often become models for how we think about this period. Such broad narratives are problematic and deprive the period of its abundant intricacy. Despite such deficiencies, these master narratives are necessary within the field because historians need tools to condense the immensity of human history. One way to manage this enormity is to construct general timelines and accounts of multifaceted historical periods that are then abbreviated into digestible portions. Yet, there are real downsides when historians elect to employ that tool. Akin to foundation myths, all-embracing accounts of past epochs lose the abundance and complexity of that period. Accordingly, if historians and the general public do not occasionally step back to examine these narratives more closely, we will lose many of the contextual details that make the study of history so intrinsically fascinating. For this reason, it is essential not to let these broad narratives take hold within the collective imagination of the public or, even, within academia circles.

The consequence of this historical detaching is that the easily palatable archetype often becomes the basis for a historical narrative that becomes entrenched within the minds of the general public. Of course, this popular imagining is an inaccurate account of those events and disregards the rich complexities of human history. Such notions also present problems for historians when attempting to peel back the layers of history to get at the heart of the event or period. There are genuine fallacies that serve to mislead historians when they attempt to examine the past. Historians have often been ensnared in the pitfalls of these sweeping historical narratives, which drain the period of its bountiful intricacy. In so doing, historians often neglect to account for the fact that only individuals act. While there are popular trends in history that move entire communities into action, one must remember that each individual in that society had to choose to go along with that collective action. Thus, it is the central task of the historian is to attempt to explain why those individuals acted in the ways that they did and to understand the various elements that influenced that individual to make that decision.

As follows, one should consider the stereotypical impulse about the American War of Independence that is instantly summoned to one’s mind when one thinks about those who remained loyal to King George III. When imagining a Tory or a King’s Friend, instantly an image comes into the focus, a male of aristocratic origin, wealthy, wearing a powdered wig, and dressed in the finest clothes fresh from London. The image in one’s mind may even evolve further; one may invoke the fleeting whisper of a gentleman of the King’s government who sneers at the pathetic protestations of a bunch of vulgar provincials that are always complaining about their supposed rights as Englishmen. Perhaps one even puts a name to that image, the infamous Thomas Hutchinson or William Tryon. Yet, do these common archetypes of loyalists form a truthful portrait of the average Tory in Colonial America? The answer to that question is a qualified no. The Founding Generation of American historians, who record the experiences of the war during the early to mid-nineteenth century, handed down many of these historical generalisations. Consequently, such notions have their origins in the master narratives of the period. While it is true that some Tories did fit into the aforementioned category, certainly not every individual Tory can be placed in the same class of loyalist as the maleficent and rapacious William Tryon.[3]

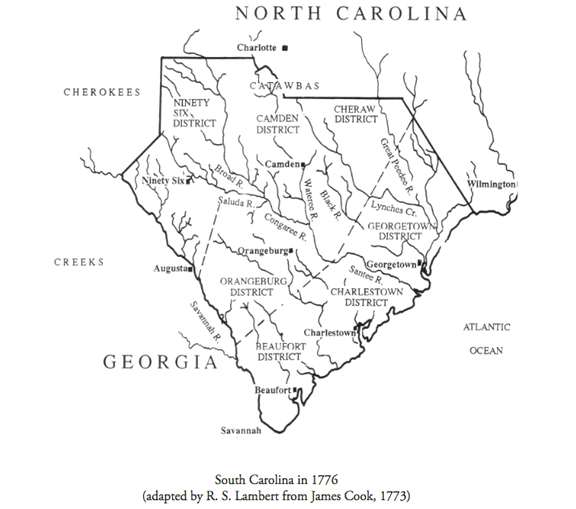

In truth, Loyalists came from all levels of colonial society, just as the same can be said of those on the Patriot side. Indeed, from colony to colony, different kinds of people chose one side or the other depending on local circumstances and individual reasons. For example, in New York, the majority of the large landholders tended to remain loyal, while in Virginia the same group tended to support the Whigs. Likewise, in New England, farmers of small landholdings tended to be Patriots, while in the Backcountry of the Carolinas they were inclined to remain loyal to the Crown. Evidently, an individual’s loyalty varied region by region, depending on local conditions. In addition to regional variances, there are several different types of people who were inclined to become loyalists. The first category fits into the popular narrative, a person of some means that has connections to the Metropolis whether by governmental appointment or through dependent commercial ties. The second type of person who tended were religious or ethnic minorities. These persons sought the protection of the Crown to ensure their continued existence within the Empire. The third type of loyalist tended to be recent immigrants. It is posited that the immigrant loyalist chose to side with the Crown because they felt that the British government could ensure their landholdings and they were not in the colonies long enough to socially integrate into the communities that they recently arrived in. The final category of loyalists consists of those who lived on the edges of colonial society and away from the ideological centres of the Whig movement.[4]

While past historians have, for the most part, adhered to the abovementioned general framework, more recent historians writing on the subject of loyalism have openly admitted that the elements that factored into an individual’s motives for remaining loyal are inherently complex.[5] Nonetheless, when some of these historians offer an example of a loyalist they, more often than not, use the type of loyalist that is in the first category, which is comprised of individuals from upper rungs of colonial society, who have governmental or mercantile ties to the Metropolis. To highlight one recent example, in Maya Jasanoff’s book, Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World, she admits that loyalism was a multifaceted phenomenon. Nevertheless, she then trots out the loyalist archetype of Joseph Galloway, and others who are comparable, to serve as the main illustrations of loyalism. The use of prominent loyalists as examples is problematic because Joseph Galloway’s experience teaches little about the average loyalist. Apart from the common elements of loyalty to the Crown and their participatory victimisation at the hands of the Whigs, the Galloway archetype tells us little about those of the “common herd” or “middling sort.” Hence, not much can be compared to the experiences of elite loyalists and the ordinary loyalist that does not fit into those well-ordered categories. Moreover, Jasanoff oversimplifies the forces that influenced individual decisions to support one side over the other. Jasanoff states that “[w]hat truly divided colonial Americans into loyalists and patriots was the mounting pressure of revolutionary events: threats, violence, the impositions of oaths, and ultimately war.”[6] With this assertion, Jasanoff is neglecting to acknowledge the intricate factors that shaped the thought patterns of individuals as they deliberated upon which course to take.

Only a hand full of historians have even broached the question of what factors drove these individuals to support the King against their fellow colonists, which is also problematic. When attempting to determine the individual motivations of loyalists, the task seems as if it is an exceedingly monumental endeavour for historians to compress such a thorny subject into a digestible narrative. As a consequence, many historians merely state that the motives of loyalists are too diverse to define and, thus they do not even attempt to address the issue. To provide an example of this type of evasion it is prudent to return to Jasanoff. Instead of addressing the possible reasons for a colonist to support the King, Jasanoff pivots away from the problem by merely stating, “[u]ltimately choices about loyalty depended more on employers, occupations, profits, land, faith, family, and friendships than on any implicit identification as an American or a Briton.”[7] As one can discern, Jasanoff’s statement clearly lacks substance, then the text quickly moves on to more tangible and less elusive matters that support her narrative. Despite such avoidances by some historians, others have vigorously attempted to confront the issue of loyalist motivations directly. The dominant historian among this group is Robert Calhoon, who had been writing about loyalism since the late 1970s. Working in conjunction with other Loyalist historians, Calhoon compiled a compelling set of factors that determined whether individuals allied themselves with the Whigs or Tories. Restating the common problem inherent to any study of human action, Calhoon argues that “[o]ne of the things we still know far too little about is Loyalist motivation…motivation can only be inferred from behavior. But a careful analysis of the circumstances in which it occurred, can tell a great deal. And although not conclusive, this “behavior in context” approach is the best guide we have to understand the mind of the ordinary Loyalist.”[8] Calhoon’s “behavior in context” methodology is part of the loyalist calculation, though he classifies loyalism into five broad categories, he does offer the admonition that there is no general framework that can account for the stimuli for some ten thousand loyalists who actively took up arms for the Crown during the conflict.[9] That assertion is significant and is one that needs to become a historical intonation. The conventional narrative on loyalism can only be corrected when the intricacies of that phenomenon become a mantra that gets repeated in university lectures, secondary school textbooks, and within popular historical works.

Loyalism: A Convoluted and Inconsistent Narrative

With the above-mentioned points in mind, the task for current historians of the War of American Independence is to counter these conventional narratives and to conduct multiple objective inquiries that focus on the local conditions that produced the various elements that compelled individuals toward Loyalism. Calhoon, maintains that is it only by taking local circumstances and placing them into the broader context of the period, may one be able to discover the underlying currents that influenced Loyalist thought. Calhoon’s observation strikes at the very heart of the matter by bringing a series of focusing lenses upon local contingencies, which offer the intrepid seeker of truth a logical way to approach Mackesy’s nightmare world.

Following Calhoon’s lead, one must delve deep into the historical record in order to uncover information about who these people were, whom they associated with, where did they live, what was the communal composition, and what was their socio-economic backgrounds. To that end, Esther Wright’s study of the New Brunswick Loyalists and Maya Jasanoff’s extensive account of Loyalists within the British Empire offers us tantalising hints into the lives of those persons that chose or were forced into exile after the conflict.[10] From studying various groups of exiles, it has been observed that Loyalists came from all rungs of colonial society. Some twenty thousand to sixty thousand[11] Loyalists left the former colonies throughout the war. However, even if one takes a moderate number of forty-five thousand Loyalist exiles that still leaves a significant number of individuals who stayed in the former colonies after the war. That point in of itself is most intriguing and produces a deluge of questions. Despite the author’s curiosity as to the reasons why the vast majority of Loyalists stayed, such inquiries are beyond the scope of this rumination.

Given that such a substantial portion of Loyalists stayed in the newly established United States, roughly four hundred and fifty thousand, how do we attempt to discern the total population of Loyalists? In an attempt to address this question, historian Paul Smith’s examination of Loyalist militia forces during the war has done much to increase our collective understanding of the actual numbers of Loyalists who actively fought for the British. Using Lorenzo Sabine’s classic biographical collection of six thousand individual Loyalists,[12] Smith’s quantitative study determined that fifteen per cent of Sabine’s Loyalists served in provincial forces during the conflict. He then applied that measure to all Loyalists using a 1:4 multiple per family, which equates to a figure near nineteen thousand men who saw active military service with British forces. Building upon that number, Smith extrapolates that between 1775 and 1783, around five hundred and thirteen thousand Loyalists were living in the colonies.[13] Since the publication of Smith’s work in the 1980s, historians have generally accepted this number as a satisfactory estimate of the strength of Loyalist sentiment within the Colonies.

On the other hand, Smith’s data is incomplete regarding militia service numbers, and the figures are not proportional to areas with a high concentration of Loyalists. In Robert Lambert’s study, South Carolina Loyalists in the American Revolution, he calls attention to a glaring issue with the numbers regarding South Carolina. Lambert notes that Smith does not incorporate the militia records and only utilises data on the South Carolina Royalist regiment, which infers that the Loyalist population was considerably more significant in the state than is suggested by the figure that Smith calculated.[14] Even with those observations, historians still struggle to explain and understand what motivated Loyalists to side with the Crown, let alone why some of those same Loyalists chose to stay after the war. Calhoon asserts that “[n]o simple formula can account for the nearly 10,00 loyalists who bore arms during the first half of the war.”[15] Thus, in order to glean a more accurate understanding of the era, historians must ask some serious questions about the motivations and activities of individual Loyalists during the war. For instance, does the traditional jingoistic explanations of Loyalist motivations apply to all of those who choose to side with the Crown? If not, are there common elements that define loyalism? Or is the source of Loyalism purely individualistic in nature as Calhoun contends? What were the reasons behind individual Loyalists’ decision to take up arms for the Crown and against their neighbours? Were their decisions grounded in personal relationships, social circles, religious convictions, or socio-economic reasons? Or was the choice a culmination of these elements?

Given the complexities inherent within Loyalism, and in order to answer the lingering questions concerning the multifaceted influencers on individual decisions, historians must begin their examinations at the local level. Only by combining geopolitical factors with local economic and social considerations, will one be able to observe the reasons why common colonists rejected portions of the principles that underpinned the Revolution. [16] Accordingly, the individual decision to remain loyal to the Crown was a multifaceted one that incorporated four essential determinates: extent of social integration, religious affiliation, bonds of patronage and familial ties, and personal interest. By investigating these multidimensional aspects, one will be able to glean insights into the individual thought process that facilitated an individual’s decision to take up arms against their fellow countrymen and to remain a King’s Friend.

A King’s Friend: A Portrait of Captain Alexander Chesney

Writing in 1783, the Reverend Archibald Simpson commented that “All was desolation…Every field, every plantation, showed marks of ruin and devastation. Not a person was to be met in the roads. All was gloomy”[17] An equally shocked Continental Maj. William Pierce recounted the extent of the violence in a letter to St. George Tucker,

“Such scenes of desolation, bloodshed and deliberate murder I never was a witness to before!…Wherever you turn the weeping widow and fatherless child pour out their melancholy tales to wound the feeling of humanity. The two opposite principles of whiggism and troyism have set the people of this country to cutting each other’s throats and scarce a day passes but some poor deluded tory is put to death at his door.”[18]

Revenge killings, retaliations, rapine, and unabashed murder raged across the backcountry. Of the one hundred thirty-seven major engagements in South Carolina, seventy-eight were fought in the up-country. The wanton destruction within western borderlands was more brutal than in the relatively peaceful Low counties. Significant portions across the Saluda River region, Ninety-Six, and the North Branch of the Broad River were but smouldering ruins. Consequently, during the waning years of the war, many people living in South Carolina observed destruction wrought upon the landscape and asked one another; how did it come to this and who was responsible? When emerging from the trepidation of an unrelenting intercommunal conflict such questions are prudent to ask and reflect upon the responses. Even so, the answer to the question of who was responsible was simple their neighbours, kith, and kin committed these terrors upon their communities. Attempting to answer the first portion of the question of how did come to this, is more complex and requires further examination.

South Carolina historian Robert Lambert contends that “[t]here are few specific clues to explain individual and group motivation toward Loyalism in the interior of the province before 1775.”[19] Yet, there are indicators that can be observed within individual cases that partially enable us to glean insights into how events escalated. Accordingly, it is prudent to analyse the experiences of Capt. Alexander Chesney in order to understand why he elected to remain loyal to the King and what were the factors that drove him to commit acts of brutal violence against his neighbours. The account of Chesney’s life during the unrestrained years when the British shifted the War of American Independence to the South was transiently recorded by his own hand. Chesney’s journal is important because it offers posterity a critical Loyalist account of the pernicious violence that occurred through the Backcountry during the Southern Campaign. Captain Alexander Chesney was the adjutant to Maj. Patrick Ferguson and fought at the Battle of King’s Mountain (October 7th,1780), where he was taken prisoner after the surrender. Upon escaping Whig custody, Chesney served as Colonel Banastre Tarleton’s guide during the march to catch General Daniel Morgan and served as the commander of the Tory militia during the battle. While brief, Chesney’s account of the Battle of Cowpens (January 17th, 1781) stands as an important counter-narrative to Tarleton’s obfuscating explanation of the defeat as an “unaccountable panic extended itself along the whole line.”[20] Despite these insights, Chesney’s journal is also problematic if one is attempting to understand what motivated him to fight for the Crown because he never explicitly states his initial motivations. The Chesney family had every reason to loathe the British for their treatment at the hands of their English landlords in Northern Ireland, despite this fact he opted to support the Loyalist cause. Though from a humble background, Chesney, in the waning years of the war, had positioned himself within the highest circles of Loyalist hierarchy in South Carolina. The culmination of these intrigues serves to single out Chesney as a prime candidate for further examination. In so doing, one may glean insight into some of the answers to the pressing questions surrounding Loyalism.

Alexander Chesney’s story began in the bustling market town of Ballymena, in Country Antrim, Ireland. Nestled in the gently rolling moorland of Antrim, the village of Ballymena was born out of violent religious struggles of the seventeen-century. Charles I granted the land of the township and most of the surrounding countryside to William Adair, Laird of Kinhilt. Adair was a minor Protestant laird from the area around Portpatrick in the Southwest region of Scotland. Adair began importing Presbyterian Lowland-Scots families into the area to work as tenant farmers, as well as to ethnically cleanse the local Irish Catholics.[21] Robert Chesney, Alexander’s father, was born on a small tenant farm in the Dunclug portion of Ballymena in 1737. Though, it is unclear if the Chesney’s were Protestant settlers or if they arrived in the region during the Norman invasion of the late twelfth century. The surname of Chesney is a form of the French name De Chesneye, meaning oak. The name McChesney does appear within the Chesney family Bible.[22] Regardless of the family’s true origins, Alexander states that the family’s tenant farm was becoming too constricted for his father’s growing family. As a consequence, Robert Chesney then moved the family a short distance away to another tenant farm near Clough. But, after five years in Clough their situation had not improved. Facing increasing rents and violent removals, the patriarch elected to follow his kinsmen and immigrate to South Carolina on the 25th of August 1772.[23]

During the gruelling seven-week crossing of the Atlantic Ocean, smallpox broke out on board the small vessel. As illness burned its way through the passengers, Chesney’s eight-month-old sister, Peggy, died from contracting the disease and her lifeless body was given to the sea. The Chesney’s situation improved little upon arriving in Charleston, a surgeon examined the passengers and, with some trepidation, determined that they had to be quarantined. The passengers were made to “ride Quarantine” aboard the vessel for another three weeks while the pox raged throughout the ship. Once allowed ashore, they spent another three weeks at a hospital on Sullivan’s Isle. As the virus had dissipated and those that had survived recovered, the passengers were allowed to enter Charlestown. Chesney describes the chaotic scene as eager settlers roamed about the town gathering supplies and heading out for the frontier as soon as wagons were made available.

During this time, the Chesney’s engaged Mr John Mille of Turkey Creek to guide them to Jackson’s Creek, a two hundred and twenty-six kilometre journey, for the equivalent of one penny per pound of weight. Not far off from the Chesney’s new homestead, near Winnsboro, lived their cousin, Jane Cook who was married to a notable Loyalist Col. John Phillips. Moving to areas where one has kinsmen was and is still a common behavioural trend among immigrants. Having kinship ties in the area facilitated the ease of an immigrant’s transition to their new environment and these familial bonds served as the foundation for building bonds of trust or wariness with their new community.[24] Upon arrival at Jackson’s Creek, Chesney recounts that the family surveyed one hundred acres. They then began to clear some land and built a cabin.[25] At some point during the land clearing, Robert Chesney received a letter from his wife’s sister Sarah Cook, who lived just north of the Pacolet River, thirty kilometres above the Pacolet’s junction with the Broad River.

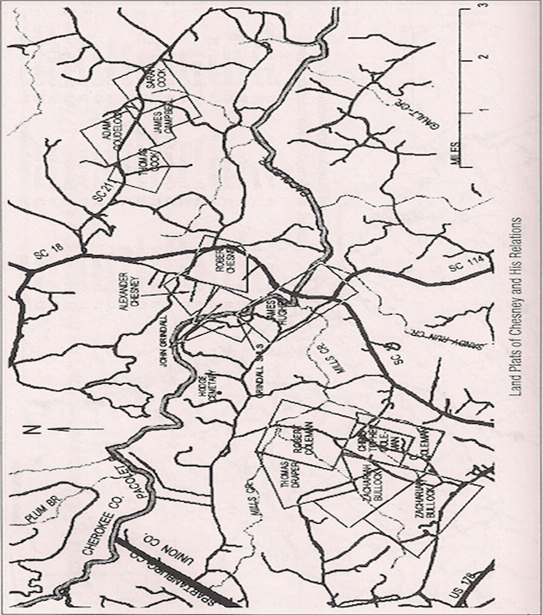

The contents of the letter are not revealed within Chesney’s journal. Nonetheless, it must have contained information about available land that was located in the fertile river bottom on the banks of the Pacolet River near Grindal Shoals. The plot of land was a further one hundred kilometres into the Backcountry and was within the Governor’s Irish Plot. Sarah Cook and her extended family had migrated from Pennsylvania in 1772 after the death of her husband John Cook. The Cooks were granted three hundred and fifty acres on the north side of the Pacolet River and Huge Cook was granted land a short distance away on Thicketty Creek. Chesney made his way to the area where he remarked that the family was “remarkably civil” and noted that a great many of the settlers in the area held the Cooks in high regard. In the conflict to come, John and Huge Cook, along with their brother-in-law Charles Brandon, would become leading Loyalists in the Grindal Shoals community.

With the assistance of the Cook’s, Alexander Chesney surveyed three hundred and fifty acres of land on the lush north bank of the Pacolet River at Grindal Shoals. [26] The land was bounded by the properties owned by John Grindal, Jacob Mitchell, John Elliott, and John Williams. The Chesney family’s land was granted on the 4th of May 1775. Alexander was granted one hundred acres adjoining his father’s land, which was on the 31st of May 1775. Once the surveying and documentation had been completed, Alexander and Sarah Cook’s sons assisted the remainder of the Chesney family in moving to their new homestead on the Pacolet. The Chesney’s also boarded with the Cooks until the families’ cabin was built. From 1773 on, the journal briefly recounts the daily goings on of clearing land, planting crops, and building the family’s cabins. Chesney dryly states that, apart from the birth of two more siblings, life went on “without any particular occurrence…until 1775” when William Tennent arrived to present the Whig association to the inhabitants of the region at the Thicketty Creek meetinghouse.[27]

From these brief journal entries, one can clearly observe how important these ties of kinship were to immigrants and these relationships would form the foundation of familial allegiances. As the political disagreement over the nature of the Rights of Englishmen and the structure of British Imperial Federalism escalated into open violence, Chesney states that he provided services as a guide and sheltered fleeing King’s friends from Whig militia under the command of Col. Richardson during the Snow Campaign of 1775. He even went so far as to go to Col. Richardson’s main encampment in the Congaree region to guide defectors like Capt. James Phillips and his militia company to the relative safety of Loyalist held areas in North Carolina. It was during this period of Whig domination that the Loyalists of the Pacolet River area formed an association to gather support for the King’s government, as well as for mutual protection.[28] Shortly thereafter, it seems both Robert and Alexander’s activities were discovered and his family’s property “ransacked”. Whig forces caught both men, in the act of sheltering Loyalists and were immediately imprisoned at the Whig camp on the Reedy River. Col. Richardson paroled Chesney but the “Congress party” held him in contempt.[29]

Alexander was given the option to return to his cell or affirm his loyalty to the South Carolina Provincial Congress and join the “Rebel Army.” Lacking another recourse, Chesney plainly states that he chose to serve in the Whig militia to “save my father’s family from threatened ruin [.] He had been made prisoner already harbouring some Loyalists.”[30] Seeing the reality of the situation, Alexander forsook his professed loyalty to the King in exchange for the safety of his kith and kin. Chesney’s kinsman John Cook would take a stand on principle and not swear an oath to the Whigs. As a result, Cook was brutally whipped in public and imprisoned until liberated by the British after the capture of Charlestown in 1781.[31] Chesney’s actions at this point suggest that he was not yet motivated by an overt adherence to abstract principles, but rather, as many in the Backcountry, by survival, which meant they would support whatever side held the upper hand at any given moment.

With his loyalty now declared for the Whigs, Chesney served as a private in the militia at the first the Battle of Charlestown (June 4th-28th, 1776), where he and a few friends attempted to defect to the British lines but were unable to secure a boat, so abandoned the effort. From Chesney’s actions, one might conclude, as Ralph Waldo Emerson did when he wrote, “[a]ll promise outruns the performance. We live in a system of approximations. Every end is prospective of some other end, which is also temporary; a round true, not domesticated.”[32] Emerson’s point highlights the endless possibilities that might explain human action. Was Chesney an opportunist seeking a way to further his own ambitions? It might also be true that he seems to have been suffering from the rashness of youth. Or perhaps he truly was a principled friend of the King. Regardless of the underlying motivation, one has to wonder if he thought through this decision to defect to the British. Did Chesney consider what would happen to his father’s family if Major General Charles Lee’s forces discovered that he had defected? When not in the tempering presence of his father, Alexander does not seem to have been aware of how the consequence of his actions would affect those associated with him. This rash disregard for others is a theme that is recurrent throughout Alexander’s journal.

After this episode and the failure of the British to capture Charlestown, Chesney was sent on a campaign against the Cherokees and Creeks in the Lower towns then shifting north to burn the Valley Towns. Remarkably, Chesney, rather matter-of-factly, states that his unit had little opposition in fighting the aboriginals despite a near-miss at a “serve battle with Indians near the middle settlements.”[33] During the engagement, five or six Cherokee levelled their muskets at Chesney. One marksman amongst the group nearly hit his mark but for a small tree branch that slowed the ball to the point that it lost all momentum before striking his chest. Despite a near-death experience, Alexander dryly attests that during the summer of 1776 he assisted in devastating thirty-two aboriginal villages under the command of General Williamson and Col. Sumter.[34] Ostensibly indifferent to the carnage he had just engaged in, Alexander’s journal picks up in the spring of 1777. One observes Chesney on what might be considered a grand colonial tour, with him participating in target practice upon Alligators and enthusiastically skirmishing with the Creeks in the swamps around Fort Barrington on the Altamaha River in Southern Georgia. Indeed, it seems that Chesney, like many Ulster Scots, had a particular disdain of aboriginals, he plainly states “we had several scrimishes [sic] with the Creek Indians, in which I was always a volunteer.”[35] This admission about his eagerness to assail native peoples is a curious one because he had only lived in the colony for about four years and had not experienced the pitiless fighting during the Seven Years War. Moreover, it also seems strange that Chesney would be so active in the suppression of the King’s allies.

From this account we can only conclude two possible reasons that account for Chesney’s behaviour. Firstly, Chesney’s explanation supports the idea that he was an impressionable twenty-two-year-old at that time, who was out on his first campaign and was merely emulating his superiors to curry favour as young men are often inclined. The second reason may be informed by the experiences of the Cook family who lived on the Pennsylvania frontier during the latter part of the Seven Years War. Given the bonds of kinship, Chesney would have been told the Cook family accounts of the terror and havoc wrought by the tribes during the war. With lineage from a people with long memories, perhaps the occasion presented an opportunity to settle old feuds. If the second reason provided the impetus for Chesney’s actions, then it is another example of how familial relations and heritage can shape an individual’s mentalities. As opposed to the rational notion that stipulates if Chesney were a true friend of the King, it would be counterintuitive to attack your potential allies so vigorously.

Regardless of Alexander’s underlining motivations, he had served across the Backcountry of Georgia and the Carolinas in the service of the Whigs. After spending an uneventful winter at his farm along the Pacolet, the spring of 1778 found him under the command of his neighbour Captain Zachariah Bullock and was promoted to lieutenant by his “loyal friends” within his militia company.[36] Chesney remained under the command of Capt. Bullock and Capt. McWhorter in Georgia. During the summer of 1779, his militia company was skirmishing with the Creek before being ordered to march up from Augusta to reinforce General Lincoln’s forces at Charlestown. Stationed in the fortifications along the Stono, Chesney states that just before Lincoln’s attack on the British lines at the Stono River, he “returned home on business.”[37] It seems that Capt. Bullock found the young Lt. Chesney dependable enough to send him back to Grindal Sholas to recruit. This brief entry is another curious statement given that the Battle of Stono Ferry (June 20th, 1779) was the last major engagement before the siege of Charlestown began the following year. The timing of Chesney’s departure from Bullock’s militia company is curious, he seems to have been content with rampaging against aboriginals but through some stroke of luck or contrivance, he avoids the Battle of Stono Ferry, which would place him in direct opposition with British forces. Regardless of the circumstances, he returns to his homestead on the Pacolet River and is engaged to marry the daughter of a local Whig family, The Hodges. To further muddy the matrimonial waters, Elizabeth Cook, cousin of Alexander, married The Hodge family’s patriarch, William II. Accompanying Margret Hodge in the marriage is her dowry of two hundred acres of prime bottomland. Reflecting upon this marriage, one finds it to be peculiar that a Whig family would allow their daughter to marry a “former” Loyalist. Interestingly, marriages between families on opposing sides seem to have been a fairly common occurrence. Indeed, Alexander Chesney’s sister Jane married Daniel McJunkin, the brother of a prominent Whig named Joseph McJunkin.

After Chesney’s marriage to Margret Hodge, he does not return to the militia and states that it was “firmly believed in the beginning of the year that Charles-town would be reduced by the British.”[38] In due course, Charlestown fell to the British on the 12th of May 1780. In short order, Gen. Clinton issued three decrees to facilitate “tranquility and order to the country.” On the 22nd of May, Clinton pronounced that anyone found in arms or persuading “faithful and peaceable subject” to rebel against the King would suffer imprisonment and the confiscation of their estates. The next decree was issued on the 1st of June, which offered amnesty to all those who swear an oath of allegiance to King George III. Not two days later, Clinton issued an amendment to his proclamation requiring all paroled militia to swear an oath of allegiance within seventeen days and were henceforth required to take up arms in defence of the His Majesty’s government in South Carolina. Whigs considered these proclamations as deceitfulness on part of the British because it meant that they could no longer continue their lives as neutrals in accordance with the terms of their parole. These former rebels would be obliged to serve in Loyalist militia units against their former comrades, who opted not to accept Clinton’s terms. The consequence of Clinton’s decrees was that, in the span of a few weeks, the temperament of many within the South went from mild acceptance of the British occupation to active military opposition, as Loyalist militias began to seek retribution against their Whig neighbours for the injuries incurred during the Snow Campaign. Unable and, in many cases, unwilling to prevent Loyalist depravations, the British Army stood by while the Backcountry began to be set alight with the renewed flames of inter-communal strife.[39]

Upon hearing the first pronouncement, Chesney did not wait for Gen. Clinton’s June decrees to seek amnesty. On the 25th of May, Chesney submitted himself to Capt. Isaac Grey of the South Carolina Royalists, and retained his commission of lieutenant in the militia. From that point on, Chesney fought for the Crown and, in time, would become a prominent Tory militia commander. With the deceptive cloak removed, with zeal Chesney began seeking out and contending against his former comrades in arms. Within the span of a few months, Chesney had demonstrated his commitment to the British cause by accepting dangerous missions for which he would take no reward. When his loyalist neighbour, Col. Zachariah Gibbs, offered Chesney a handsome reward for accepting a mission from Maj. Patrick Ferguson to reconnoitre a Whig encampment in North Carolina, Chesney states “I told Col. Gibbs that what services I could do were not with any lucrative view and that I would undertake this difficult task for the good of H M Service.”[40] After sending that report by messenger to Maj. Ferguson, Chesney was captured at his home by his Whig neighbours, which included another brother-in-law, Joseph McJunkin, and repeated turncoat, John Heron. Demonstrating a talent for the daring getaway, Chesney would make the first of his bold escapes and return to Ferguson’s encampment to discover that his information led to the Second Battle of Cedar Springs (August 8th, 1780) which resulted in a tactical draw. Both sides claimed victory, but the Loyalist’s forces suffered the majority of the casualties. Regardless of the battle’s outcome, Maj. Ferguson was impressed by Chesney’s actions and prompted him to the rank of captain and made him the adjutant general of the Loyalist militia battalions under his command.[41]

Chesney would spend the summer and early fall fighting in a continual set of running skirmishes with Whig forces. Such was the regularity and ferocity of the fighting that Alexander admits that he could not recall the details of all the engagements, “numerous other skirmishes having escaped my memory, scarcely a day passes without some fighting.”[42] With the arrival of October, Chesney recounts that he was accompanying Maj. Ferguson in North Carolina clashing with small detachments of Whig militia in the foothills of the Blue Ridge. It was during that expedition that Maj. Ferguson issued his infamous proclamation intended to strike fear into the paltry Whig partisan bands and to rally Loyalist support. Perhaps imprudently, Ferguson boldly proclaimed in a message to Col. Shelby “If they did not desist from their oppositions to the British arms, he would march his army over the mountains, hang their leaders, and lay their country waste with fire and sword.” Ironically, Ferguson was echoing similar rhetoric and threatening violence of action that subdued his native Scotland not thirty-five years prior. Incensed by this threat, frontiersmen from all over the Appalachia began to gather in large numbers and struck out to catch Ferguson before he had the opportunity to link up with the main body of the British Army under the command of Gen. Cornwallis near Charlotte.[43]

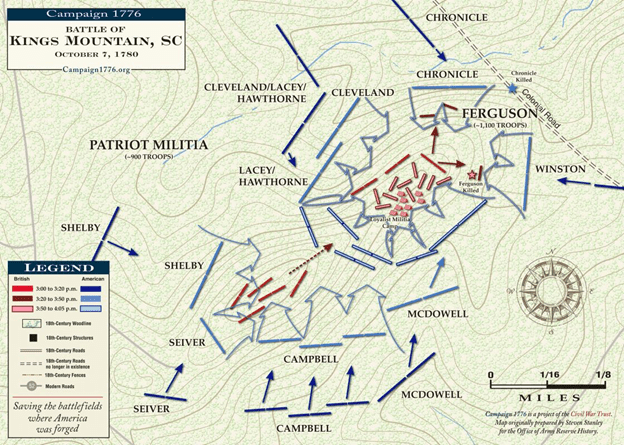

Upon hearing of such a large Whig force moving swiftly to intercept him, Ferguson sensibly decided to withdraw to higher ground. Ferguson chose a bald hill called King’s Mountain to make his stand against the approaching Whig rabble. Rising nearly one thousand meters above the rolling piedmont, the hill has a long escarpment running the length of the summit, which is wider at the northeast end of the hill. The slopes of the hill are covered in a dense temperate forest, making the terrain an ideal for militia’s “Indian” tactics, which made effective use of the rifle and available cover behind trees. Ferguson, believing the height advantage prohibited the Whigs from being able to fight their way up the steep wooded slopes if under fire, merely thought that if they got too close to his lines the bayonet-trained troops would simply push them back down the hill. Unbeknownst to Ferguson, militiamen had long observed effects of ball trajectories in relation to firing up or downhill. When firing uphill, it was observed that the ball flies on an almost straight flight path before arching as the ball loses momentum. Conversely, when firing downhill it is the natural tendency of the shooter to overshoot the target. To correct this issue the shooter needed to aim lower on the target in order to gain a hit. Nurturing the Whig militia’s marksmanship was the fact that Ferguson’s Provincials adorned in their green uniforms would have been silhouetted against the blue sky standing atop the hill while charging down at the Whig militiamen, which would make fine targets for the rifle-armed over-mountain men.[44]

From the onset of the battle, Ferguson made many tactical blunders that would cost him his life and the lives of two hundred and ninety of his men. Ferguson planned to use the bayonets of his American Volunteers to drive away concentrations of Whig militia below the hilltop, which was the standard tactic at that time in dealing with rifle-armed troops. Such tactics work well when driving a force in one direction during a mobile engagement but served little purpose during a static defence. Indeed, such needless running about only served to wear out his men and continually expose them to accurate rifle fire. Physical exhaustion when combined with persistent exposure to fire has significant negative consequences for soldiers. Moreover, Ferguson did not use the terrain to his advantage. Though thickly forested, Ferguson did not order his men to cut down trees to construct an abatis to provide defilade for his troops. In its place, he ordered that the wagons and baggage be formed as a barrier along the northeast crest of the hill where he established headquarters. He then deployed his men along both sides of the hilltop to await the attack of the over-the-mountain men.

The attack came as Chesney was demounting his horse to report to Maj. Ferguson “that all was quiet and the pickets on the alert.” The report of rifles was heard on the northern slope of the hill, Chesney rallied his militiamen and was wounded above the knee during the first exchange of fire but remained to perform his duties. Darting from behind trees and firing, Whig militiamen inflicted heavy casualties on Ferguson’s men. Chesney sorely described the “irregular destructive fire” that cut down his men. When groups of Whigs would get close to overrunning the Loyalist militia, Ferguson’s American Volunteers would perform a bayonet charge downhill to dislodge the Whigs. This tactic had a limited effect because once the provincial troops moved back up the hill the rifle-armed Whigs would follow and pick off Ferguson’s men as they climbed back up the slope. In one last valiant attempt to rally his men for a breakout, Ferguson was shot from his horse. His foot being caught in the stirrup was dragged a distance and his red-checkered shirt made him a perfect target for numerous Whig marksmen, each wanting to exact their personal revenge on the man who had threatened to burn their homes. “Upon examining the body of their great chief,” wrote James Collins, “it appeared that almost fifty rifles must have been levelled at him at the same time; seven rifle balls had passed through his body; both his arms were broken, and his hat and clothing were literally shot to pieces.”[45]

Throughout the battle, Chesney states that he scarcely felt the pain from his injury because he was so preoccupied. The night after the battle he tells us was a night filled with the stench of the dead and the air filled with the cries of the wounded. What is notable is the fact that Chesney does not mention the depraved acts that Tarleton attributes to the Whigs. Tarleton’s account states that the Whig militia stripped Ferguson naked and urinated on his corpse.[46] The journal of Dr. Uzal Johnson, Ferguson’s surgeon, also does not mention this heinous event.[47] It seems that only Tarleton mentions this disturbing episode of barbarism. Regardless, Chesney was taken prisoner along with some six hundred other Loyalists. On their long march back into North Carolina, each prisoner was made to carry two muskets and had his shoes removed. On the night of the 14th, Alexander watched as the Whigs hung ten prisoners; Dr Johnson mentions only nine.[48] The approach of Tarleton’s British Legion put an end to these dark festivities and the prisoners were force-marched toward the Yadkin River. Along the way, Chesney tells of how some of the Whig forces were “cutting and striking us by the road in savage manner.”[49] Eventually, the infamous and ruthless Whig commander, Col. Cleveland, confronted Chesney. Cleveland offered Chesney his life in exchange for insights into how Ferguson employed his command whistle and a demonstration of the troop movements. When he refused, Cleveland ordered him to be put to death once they reached the Moravian towns. Fortuitously, Chesney saw his opportunity to escape while on the northeast branch of the Yadkin River, around modern-day Winston-Salem.

Trekking back in the woods and accepting assistance from kindly loyalists, Chesney made the two-hundred-and-forty-kilometre journey back to the north branch of the Broad River. Once across the river, he made his way to his brother-in-law’s, John Heron, who it seems was also at King’s Mountain but fled the battle at the first opportunity by placing a scrap of white paper in his hat, which identified him as a Whig combatant. Chesney would spend the night there before making the fourteen-day journey back to his farm on the Pacolet. Once home he found that the Whigs had ransacked the house, which left his wife and infant children in a state of desperate need. Yet, Chesney seemed more concerned about re-joining British forces than caring for his young family. While potting to re-join the British, he and fellow Tories, Hugh Cook and Charles Brandon hid in a shallow cave on a branch of the Pacolet. Cook’s wife brought the men meals and news of troop movements in the area. Interestingly, he also states that he hid at his fathers-in-law, William Hodge II, who was a noted Whig. Upon hearing that Col. Tarleton had been defeated at the Battle of Blackstock’s Farm (November 20th, 1780), he attempted to raise a company “with great difficulty” and joined the assembling Loyalist militia at the home of turncoat Col. Andrew William’s on Little River. Chesney was then ordered to rendezvous with other units on the Enoree, but upon arrival at the appointed place, he was taken prisoner by Maj. Benjamin Roebuck. After a brief skirmish to free Chesney at a fortified house not far off, Maj. Roebuck paroled him to Fort Ninety-Six in exchange for Capt. Clarke, son of prominent Whig Col. Elijah Clarke.[50]

That December, Chesney was placed in command of the militia guard at the jail of Ninety-Six. With the arrival of Tarleton’s British Legion in January of 1781, Chesney was ordered to be a scout and guide during Tarleton’s race to catch Gen. Morgan. Upon entering the Grindal Shoals area, he observes the old camps of Gen. Morgan’s army. He then proceeded to his father’s house, where he was told that Morgan had gone to the “old fields about an hour before.”[51] Chesney then rushed to intercept Tarleton and found him to the north at the head of Thicketty Creek, which was Morgan’s last campsite. Upon making contact with Gen. Morgan’s mixed force consisting of militia with a small contingent of regulars at a place known as the Cowpens, Chesney sardonically comments that “we suffered a total defeat by some dreadful bad management.”[52]

Chesney asserts that a key element of the defeat was due to the observation that Tarleton’s British Legion was mostly comprised of American Continentals captured at the Battle of Camden (August 16th, 1778), and seeing their old regiment they refused to attack it. In of itself, that point offers profound insights into the complicated nature of the divided loyalties that emerged during the war. At the end of the brief account of the Battle of Cowpens, Chesney plainly states, “I was with Tarleton in the charge who behaved bravely but imprudently. The consequence was his force dispersed in all directions [and] the guns and many prisoners fell into the hands of the Americans.”[53] For Chesney, the reason for the failure of the British attack clearly fell at the feet of Col. Tarleton. Moreover, Chesney understood the implications of the British defeat at Cowpens because he rode hard to his family’s modest farm. Upon arriving, he gathered his family and what little was left of their possessions, the homestead was plundered this time by Gen. Morgan’s army a mere two days before the battle and was stripped of anything that could aid Tarleton’s men. A brief aside to examine these complex familial bonds is prudent at this juncture, males of the McJunkin and Hodge families would fight on the opposing side against Chesney. The night prior to the engagement, Gen. Morgan ordered his army to take supplies from loyalists as to not further impose upon the patriot families. It is not improbable infer that either McJunkin or Hodge had a hand in stripping Chesney’s house clean of anything of value in retaliation for his possible hand in their imprisonment in the winter of 1780.[54]

With his family in tow, they rode to Rob McWhorte’s at the headwaters of the Edisto, where Chesney left his family. He then proceeded to Charlestown to find accommodation and reparations for his services.[55] In the meantime, the Whigs had been precipitously regaining control of the areas outside British outpost and urban strongholds. By December 1782, the British found themselves largely confined to Charlestown and its immediate vicinity. During this period, Chesney was appointed to be the superintendent of cutting of wood and found some comfort in alleviating the impoverished condition of a number of refugee loyalists by employing them in this work, which prevented them from starvation. Chesney had lost his wife and infant daughter at the end of November 1781 and was obliged by ill-health to relinquish the administration of the woodcutters early in the following January. As his illness got progressively worse, he sent his son to his mother’s, who still resided at Grindal Shoals.[56]

In the late spring of 1782, Alexander would embark upon the Orestes, a British sloop of war, bound for Ireland. The name of the ship that would transport Alexander was fitting for it would carry him away from the brutal madness of civil war that had taken hold within the Carolina Backcountry. Across the tempestuous Atlantic Ocean, Chesney abandoned his kith and kin in hopes of achieving the relative stability that he perceived the Empire provided. At this point, Alexander sought compensation from Parliament for his losses at the hands of the Whigs. On May 19th, he landed at Castle Haven, Ireland, and began to seek recompense for his service. In doing so, Chesney abandoned his only surviving child and his father’s family in South Carolina. Alexander never returns to America, instead he remarries and settles down in Northern Ireland. Chesney would continue to serve his King as a minor official in Ireland, and his sons would gain some fame. This final point about Chesney’s departure is fascinating in of itself because in 1784 the South Carolina assembly passed the first Loyalist clemency act that returned about seventy per cent of the confiscated property to their original owners.[57] This clemency accounted for the fact in 1818 Chesney receives a letter from his son William, who he left in South Carolina. In the letter, William stated that he and Robert Chesney, Alexander’s father, were alive. The letter goes on to recount that they were “not in flourishing circumstances in the State of Tennessee.”[58] William’s letter to his father thirty-six years later begs the question, why did Chesney choose to abandon his infant son and extended family with such haste when he could have had most of his lands returned to him within two years? We may never know the true answer to that question. Nevertheless, it is evident from this brief account of Chesney’s involvement in the war that Loyalism was a complicated confluence of influencing factors and Alexander Chesney stands as a prominent outlier when compared to archetypes within the conventional Loyalist narrative. Thus, in order to more clearly observe those possible influencing elements, we need to delve deeper into the historical contexts that permeate Chesney’s pithy journal.

Loyalism Along the Banks of The Pacolet River

Recalling that within Peter Moore’s investigation of the Waxhaws community, he observed that within that one’s allegiance was based on four main local factors: the size of land grants, date of immigration into the region, the political leanings of kith and kin, as well as community tensions. Moreover, the study of the divide between Whigs and Loyalists within the Waxhaw community suggests that there was a high probability of a link between recent immigration and one’s decision to remain loyal to the Crown. Moore’s community-based analyses found that recent émigrés were resistant to joining the Whig resistance movement because of local socio-political dynamics between newcomers and more established settlers. These factors precluded recent immigrants’ assimilation into the community. These newcomers seemed to have all settled in the same general region and that land was usually less fertile than areas settled in the first waves of immigration into the Waxhaw region. From this one can observe the seeds of disharmony within the community over the issue of land. Furthermore, Moore notes that these immigrant areas were not ethnically and religiously diverse, which created community tensions that would serve to stoke the flames of conflict when the community was forced to choose sides upon the arrival of British regulars within the region. [59] The author will attempt to employ Moore’s framework within the Grindal Shoals community located on the Pacolet River in Upstate South Carolina.

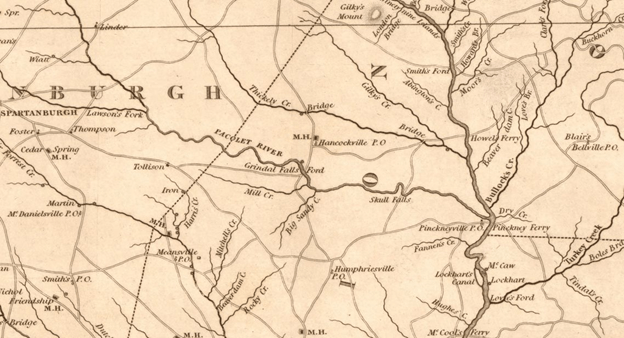

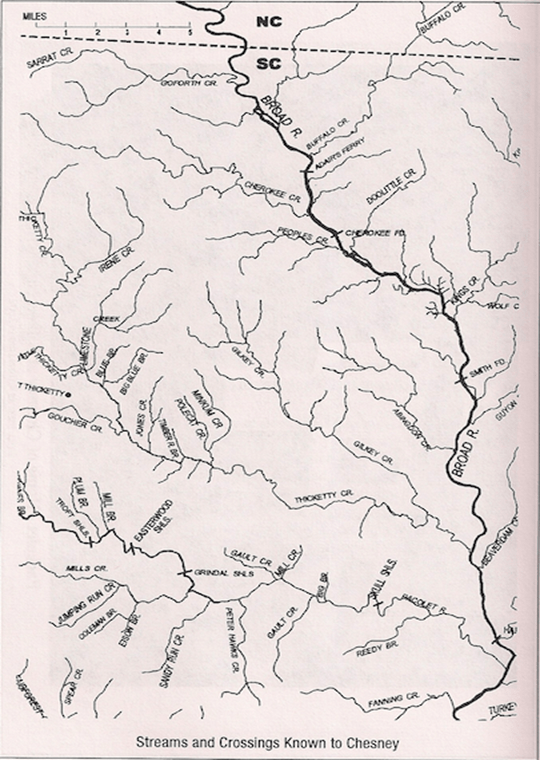

In pursuit of that end, the Loyalist region that we shall be exploring is perhaps one of the most complex and challenging areas for historians to fit into the accepted narrative. The region is located west of fertile coastal lands of South Carolina, an area that was on the periphery of colonial society. A land that was thought to have been of little consequence apart from a buffer zone between the wealthy plantations on the coast and the unruly aboriginal tribes that made their home on the western side of Appalachia. Narrowing our focus further, we observe an unassuming community spread out along the numerous streams around the confluence of the Pacolet and Broad Rivers. Located northeast of modern-day Jonesville South Carolina, the Grindal Shoals community was situated on a strategic ford that crossed the Pacolet River and was heavily used by both sides during the Revolution as the various partisans traversed the region leaving desolation in their wake.

Internal migrants predominately populated the community. In the aftermath of the Seven Years War, these settlers followed The Piedmont Road or the Upper Road from the Middle Colonies and Virginia as it separates from the King’s Highway at Fredericksburg, Virginia, and proceed south towards Macon, Georgia. However, there were also recent immigrants from what David Hackett Fischer calls the “borderlands”[60] of Great Britain, as well as a few scattered Germans. These diverse groups would consist of the ethnicities that would become known as Scotch-Irish, though the term does not entirely reflect the diversity of peoples that comprise that broad group. Many of these poor landless peoples were seeking a new life on the frontier where agents of the King were offering large tracks of land to European settlers to sever as a buffer against aboriginal tribe’s attacks and a dependent militia force to suppress slave revolts.[61]

What generates confusion about this term is the lack of historical context, which is a discussion that is most engaging but entirely too protracted for this reflection. Nevertheless, Griffin prudently notes, the term does not adequately describe the Ulster plantation protestants because that culture is not representative of the native Irish nor their cultural kin the Highland Scots.[62] The term is even more mystifying when one considers the depth of interactions that occurred between the Gaelic peoples of Alba, Éireann, and Prydain over the course of their dramatic and, frequently, unhappy history. The earliest use of the term is purported to have occurred in 1545 in reference to Domhnall Dubh MacDomhnaill as king of the ‘Scottyshe Irysshe.’[63] The term can also be seen within the English colonies as early as 1695 to describe that influx of Ulster plantation protestants and gained wide usage in colonial documents by the 1760s.[64]

Despite the prevalence of the term’s use during the colonial period, the so-called Scotch-Irish were loyal Protestants supplanted to the heart of the Gàidhealtachd from the Lowlands of Scotland, Northern England, the marchlands of Wales, and the German principalities. These diverse peoples were attracted to Northern Ireland as part of the Anglo-Norman plantation system that sought to ethnically cleanse the region of the troublesome and savage Irish, who stubbornly refused to be civilised by their benevolent conquerors. The Gaels and Gall-Ghàidheil were culturally distinct from the Ulster Plantation protestants. Indeed, the cultural elements and faith of Gaelic society would have been an anathema to the plantation protestants.[65] This extensive Atlantic history greatly affected how Gaels and Ulster protestants interacted in the densely forested Backcountry of the English colonies.

These groups were diverse in terms of regional languages and cultural identities. Nevertheless, they hailed from regions that were borderlands, where ethnic, religious, and state violence prevailed. The result of those tensions compelled many to flee those regional European conflicts or as a result of a complex economic crisis. What is significant about this point is how the two groups responded to those influences. Primarily, many German-speaking people choose the path of non-violence and peaceful cooperation. Conversely, the Ulster protestants were fundamentally shaped by the violence that encompassed their lives, which profoundly affected them as a people. Such a realisation is strongly suggestive as to a reason why they were more open to slavery, while some Germans choose not to partake in the budding but peculiar institution. Moreover, these consequences of European violence might also explain why Ulster immigrants adapted to frontier conditions more readily whereas the Germans struggled. Moreover, they tended to prefer isolation from other established dissenters and were often described as insular. On the contrary, the German speakers settled amongst those of similar ethnicity or faith. In economic terms, many Germans were semi-literate middling tradesmen, artisans, husbandmen, or yeomen framers that shaped their colonial experience in a slightly more positive light. Ulster immigrants, on the other hand, were mostly illiterate and, often, desperately poor, jack of all trades, tenant farmers. Despite these economic differences, the prospect of financial advancement incentivised both groups to hazard the tempestuous seas in search of economic opportunity.[66]

After 1778, Lord Germain, acting on questionable advice of Loyalist refugees from the Southern Colonies, shifted the war effort toward the South, which brought the loyalties of these diverse and seemly inconsequential peoples to the forefront of the conflict. Indeed, such was the concern over the question of which side these Backcountry settlers would support that the South Carolina legislature formed The Commission of Drayton, Tennent, and Hart to gauge the region’s support for the Whig cause. The commission’s findings and the subsequent reaction of the Whigs would have a lasting effect on which side the frontiersmen would support once large numbers of British regulars arrived in the colony during the spring of 1780. Such was the enthusiasm for the British cause in the up-country that it does give credence to the oft discounted notion that there was little support for the Crown in the Southern Colonies. With that said, the reasons why a person chose to be a Loyalist is a most complicated question and is not conducive to definitive answers. Nevertheless, when describing the situation in the up-country, Loyalist Col. Robert Grey observed, “The whole province resembled a piece of patchwork, the inhabitants of every settlement when united in sentiment being in arms for the side they liked best and making continual inroads into another’s settlements.”[67] As we journey along Alexander Chesney’s path towards armed Loyalism, we will find that Col. Grey’s description is the most prudent observation of what was occurring within communities across the Carolina Backcountry.

As we shall discover, where factors can even be identified, the individual choice of which side to support in the conflict is a convoluted one. Familial bonds were significant to some, while inconsequential to others. The threat of land confiscation and the lure of plunder guided the decisions of others. Regional leading men swayed some individuals by the force of their personality and reputation. For others, local animosities and personal grudges guided the dark hearts of others. There were also other more general factors such as recent external immigrants tended to become Loyalists, while native-born internal migrants were more inclined to be Whigs. There were also tensions between Christian dissenting denominations also played a role for some individuals in making their decision. The commonly accepted narrative about the almost universality of Scotch-Irish Presbyterian support for the Whig cause is not sustained when one observes outliers such as the Chesney family. Their rejection of Radical Whig ideals has its roots within the First Great Awakening and the alternations that occurred within Presbyterianism by evangelical ministers such as George Whitefield. Their Old Light Covenanting Presbyterian beliefs brought with them from Ulster rejected the New Light passions of their more established neighbours.

Of Anglo-Norman ancestry, the Chesney’s emigrated to Ulster during the English plantation period at some point in the mid-16th century.[68] During that destructive age, thousands of Gaels were forcibly displaced or transported to the English New World Colonies. The Ulster plantations were predominantly designed to destroy the Gaelic culture connections with the Gaelic Highlands of Scotland.[69] Setting aside the troubled past of Northern Ireland, this reflection will explore the intricacies of local structures: social connections between families, religion, the extent of integration, and when the Chesney family immigrated into the region. Additionally, it is prudent for one to consider how Alexander Chesney might have perceived land ownership and his rights as a subject of the King. Once these various elements are thoroughly investigated, one must hen combine these assorted threads to observe how they factored into his individual decision to choose to support one side in the conflict over the other. As those threads are woven together, we will observe a slightly hazy portrait of the underlying influences that informed Chesney’s decision to support the King. Indeed, we will find that his choice was a consequence of the combination of the factors mentioned above. Not from some rational mental assessment of the cost-benefit analyses or from abstract Enlightenment principles concerning human freedom, which were prevalent during the period. At its core, this inquiry will attempt to explain Alexander Chesney’s story and discern what lessons about the intricate influences can be gleaned about loyalism in the Carolina Backcountry from his experiences. Ultimately, Chesney’s life experiences demonstrate that his life is both representative of the ordinary Loyalist’s experience and a significant deviation from that narrative.

“Contending For the Ascendancy:” Grindal Shoals Demographics

After the fall of Charlestown in 1780, throngs of militia and banditti posing as militia roamed the countryside intimidating adherent on both sides.[70] A Whig militiaman recounted that it was “almost Fire & Faggot Between Whig & Tory, who were contending for the ascendancy.”[71] This unpretentious observation subtly conveys the scale of savagery that was unlashed in the up countries of Georgia and the Carolinas, where neighbours turned upon one another in a perpetual cycle of violence. Yet, those tumultuous events lay in the future for the Chesney Family. By the time that the family arrived in South Carolina during the autumn of 1772, the Grindal Shoals region was home to about forty-nine individuals and extended families scattered along both banks of the Pacolet River beginning at the west bank of the Broad River stretching west towards Lawson’s Fork Creek. The demographics of the region are difficult to sort out given the lack of accurate records of the period.[72] Nevertheless, by utilising genealogical accounts and existing land grant records, one can begin to observe the dispersion of the community. For this inquiry, however, it is prudent to only focus on the families that were powerful influencers within a day’s ride from the Chesney homestead. Moreover, it is also wise to employ the Pacolet as a dividing line between the families. Even with these distinctions, the intermarrying before the war has muddied the waters of the region significantly. Indeed, as this paper develops, one will observe that the familial bonds for women seem to be an inconsequential factor, and their allegiance is contingent upon their husband’s political dispositions. Thus, though extensive marriage links existed between Whig and Loyalist families, that does not seem to be a factor in individual decisions to choose to support the Whig or Loyalist causes. With that said, once the families are plotted upon a map one does observe similar familial and religious bonds that Moore found in his study of the Waxhaw’s community, though the families are not so neatly divided into two distinct areas. Instead, extended familial clusters can be observed, with male members dictating allegiances despite intermarriage with families on opposing sides.[73] Another interesting note is that it seems that within the younger males of the leading families, there seems to be no observable source for their constantly shifting allegiances, which ebbed and flowed as both sides contented for the ascendancy.

On the north side of the Pacolet River, intermingled among the numerous snaking streams that flow into Gault Creek, the Cook family choose to cut out of the wilderness a three-hundred-acre farmstead. The matriarch of the extensive Cook clan was Sarah Fulton Chesney, the sister of Robert Chesney, Alexander’s father. The Covenanting Presbyterian Cook family emigrated from Northern Ireland to Pennsylvania in the years following the Seven Years War. After the death of John Cook, the widow Sarah choose to move on to larger land grants on South Carolina’s frontier.[74] Accompanying the family was a young Charles Brandon and his wife Sarah Cook. Charles and Alexander Chesney would be boon companions throughout the turbulent period until Alexander chose exile after his wife, Margaret Hodge, succumbed to smallpox during the winter of 1781 in Charleston. [75]

Once in Grindal Sholas, the Cook family wasted little time and quickly married into prominent families already residing in the area. David Cook married into the staunchly loyal Gibbs family, whose large estates were located south of the Pacolet River near Christie’s Tavern, which was run by another leading loyalist family, the Colemans. Switching sides, Elisabeth Cook married into the leading a family that would be fervent Whigs, the Hodges. Perhaps this was a shrewd political move on the Cooks part to shore up their position in the region, which was the common practice in the Old Country. The remaining Cook children, apart from David who married Mary Gibbs (Zacharias Gibbs’s Sister) were already married and brought their spouses with them when migrating from Pennsylvania. Despite the marriage ties to a future leading Whig family, the Hodges, the Cooks would be fiercely loyal to the Crown during the coming war. All but the youngest son David and Charles Brandon choose to stay after signing an agreement that stated they would no longer bear arms against the Whigs.[76]

Straying from the Cook family’s resolute loyalism, the Chesney’s fractured throughout the war for reasons not entirely clear, and Alexander makes only passing mention of his siblings within his journal. Only the patriarch, Robert, and his eldest son, Alexander, displayed any real zeal for the Loyalist cause. Like their cousins, the Cooks, the Chesney’s were Covenanting Presbyterians, who missed the levelling consequences of the Great Awakening that occurred within the Backcountry. Alexander would follow the Cook’s lead and marry into the Presbyterian Hodge family in 1780,[77] during the short parole period before General Clinton’s order mandating all former Whigs, who been paroled, to serve in loyalist militias. The creation of this bond might have been an attempt by the Chesney family to emulate the Cooks in order to create familial bonds between the prominent families of the region. Such notions of creating political and social ties between families was an ancient European custom.[78] Nevertheless, the second oldest son, Robert Jr., would remain relatively neutral throughout the war. Conversely, the youngest son, William, just a young lad at the time of the war, would actively serve as a dispatch rider for the Whig militia. Though difficult to accurately determine, records indicate that William served with the Second Spartan Regiment under the command of Col. Brandon and Maj. Joseph McJunkin. Their sister Jane would marry into the McJunkin family, who were energetic Whigs, and her husband Daniel would serve alongside his brother Maj Joseph McJunkin in the Second Spartan Regiment.

Along with the Cook and Chesney families, on the northside of the Pacolet, were the Presbyterian Lowland Scots Goudelock family, who immigrated from Northern Ireland to Amelia County Virginia, and later to Grindal Shoals. Their property was near to the mustering grounds and the meeting house. The Officially neutral, old Adam Goudelock seemed to have harboured loyalist tendencies or at least walked a fine line between the two sides. A veteran of the Seven Years War, old Adam Goudelock would remain aloof from fighting in the years ahead. Though at crucial moments in the conflict Goudelock would support both Whig and Troy. For instance, after the Battle of Blackstock’s Farm, a doctor attended the wounds of General Thomas Sumter in Goudelock’s cabin.

Later in the war, on the eve of the Battle of Cowpens, the legendary Backcountry woodsman and notorious brawler, General Daniel Morgan, was drawing the impetuous Banister Tarleton deeper into Whig territory in order to fight on ground of his choosing. In hot pursuit, Tarleton’s British Legion swept through Skull Shoal just north of Goudelock’s cabin where Morgan’s flying column had broken camp the night before. After Morgan’s brilliant and crushing victory, Tarleton left his men and fled back whence, he came. Upon arriving at Skull Shoal, Tarleton ‘impressed’ the aged Goudelock as a guide and took him to Hamilton’s Ford after his defeat at the Battle of Cowpens. When Colonel William Washington arrived at the farmstead, Hannah Goudelock, standing on her porch that overlooked the trade road south, proceeded to mislead Washington’s pursuit by telling him that the British headed for the Green River Road. Years later when asked why she intentionally hoodwinked Washington, Hannah simply stated that she “for the safety of her husband, saved…Tarleton and the remnant of his legion from captivity.”[79] Such was the shifting tactical situation in the Backcountry that Goudelock’s daughter Sallie admits that she “had known many notable characters of the times, both Whig, British, and Tory, for her father was a lame man, a non-combatant; so it followed, his house was frequented by all parties.” It is apparent from this brief account of the Goudelock Family that another factor of Backcountry allegiance is observed: often principled loyalties are less important when your family’s survival hangs in the balance. Following this logic, it stands to reasons that loyalties shifted as the tide of battle ebbed and followed from one Whig to British throughout the course of the war.

About two kilometres north of the Goudelock’s, resided the prominent Whig family, the Jefferies. Along with the Hodge and Goudelock’s, the Jefferies were the first families to settle the region in the 1760s. Emigrating from Virginia the hardboiled veteran of the Monongahela and subsequent Backcountry campaigns against the Cherokee, Nathaniel Jefferies, and his wife Sarah Steen, sister of Col. James Steen, built a brick plantation house that was burnt by Tories during the conflict. Of English Episcopalian stock, Nathaniel and his three sons were ardent Whigs. Throughout the war, the family seems to have been in very nearly every significant engagement within their theatre of war, fighting with “splendid courage and resourcefulness.”[80] The Jefferies would serve the duration of the war within the Second Spartan Regiment under Lt. Col. Steen, and Col. Thomas Brandon, as well as in the New Acquisition District Regiment under Col. Bratton.[81]