“See that you be at peace among yourselves, my children, and love one another. Follow the example of good men of old, and God will comfort you and help you, both in this world and in the world which is to come.”

Columbkille

For many centuries, the Pictish people have been an enigma that has continually confounded definition by historians and archaeologists. Apart from the Picts’ artfully crafted standing stones and metalwork, scholars know only diminutive fragments of their culture. Nevertheless, over the last hundred years, this enigmatic society has begun to yield some of its secrets. These newfound insights are due to technological advancements in the field of archaeology, DNA analysis, geophysical survey, and more precise carbon dating. One of the most exciting re-examinations using these new tools is the excavation around the base of The Hilton of Cadboll cross-slab. These excavations have brought forth a stream of new questions, which have led to some intriguing re-evaluations of accepted knowledge surrounding the ancient peoples who carved the striking imagery on the face of the cross-slab.

Appropriately, The Hilton of Cadboll cross-slab is considered by many scholars to be one of the most excellent representations of early medieval sculpture in Scotland. Indeed, the stone is notable for the significance of its artistic quality and the intriguing narrative carved on its central panel. Despite the importance of these observable facts, there are a great many questions that still need to be answered: Who was the high-status patron that commission the work of art, and for what purpose was the stone craved? What is the significance of the surviving hunting scene relief, and what does such a scene communicate to the observer? Naturally, we may never truly know the answers to these questions. However, the ardent seeker of truth is driven to attempt to penetrate the mists of time in order to understand this stunning work on a more profound level and to decipher what message these ancient peoples are trying to communicate to their descendants, who have long forgotten their noble heritage.

Furthermore, given the renewed academic and commercial interest in this cross-slab, we should explore the proposed theories that explain the creation of the masterpiece, as well as exploring its exquisitely carved artwork in order to attempt to decode its message. Moreover, it is prudent to consider how the stone fits into the Pictish conversion to the Irish Christian faith. Taking into account the fact that Rome never conquered the majority of present-day Scotland, The Hilton of Cadboll cross-slab is an encapsulation of a moment in time when a pure Celtic religion was first confronted with alien religious concepts. Indeed, the depictions on the stone’s surviving face might contain vital insights into how local Pictish society might have intermingled traditional Celtic imagery into the new Christian paradigm. Finally, the Cadboll Stone might also provide physical evidence regarding the fluidity nature of social roles within Pictish culture. Such evidence would lend physical proof to reinforce historical texts such as the Annála Uladh (The Annals of Ulster), which demonstrates that women were free to assume a traditionally male role within Celtic societies that would be proscript in Romanised Classical Western societies.

Historical Context

Before proceeding into the multifaceted implications of The Hilton of Cadboll cross-slab elaborate imagery, it is prudent to have a concise historical account of the Picts, as scholars currently perceive the unfocused fragment of their culture, as if one is looking at a distorted image of an item resting on the bed of a rusty Highland stream. The ancestral territories the Pictish tribes occupied before the Roman invasion is ultimately concealed from modern observers. With that said, the Roman historians such as Tacitus did record that Imperial Rome never subjugated Celtic tribes north of River Tyne. Nevertheless, by 900 A.D. Pictish lands were forced north by waves of Germanic invasions to encompass the regions of the Forth/Clyde estuary and as far afield as the windswept outer isles of the northwest of Scotland. As a society that placed great emphasis on the oral tradition, Picts did not leave behind many written records of their history for their curious descendants to reveal the rich depth of their ancestry. Indeed, scant few records survived the all-consuming fires of Roman and successive waves of Christian purges. What little is known about these peoples is shrouded in mists of time comes from later Roman, English, and Irish writers, as well as from fascinating swirling imagines they carved on the faces of their silent standing stones. Lamentably, scholars cannot hear the voice of these noble peoples in their own words. Consequently, we are left stumbling around in the dark, attempting to make sense of fragments of information and ignorantly endeavouring to place those fragments into a coherent portrait of a people lost in the confusion of the debris of countless ages.

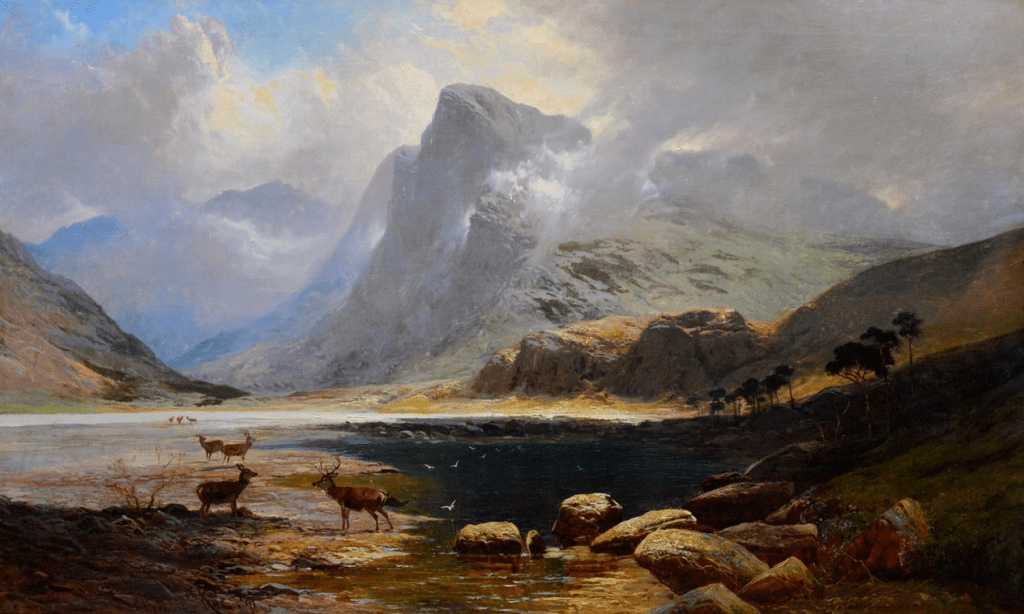

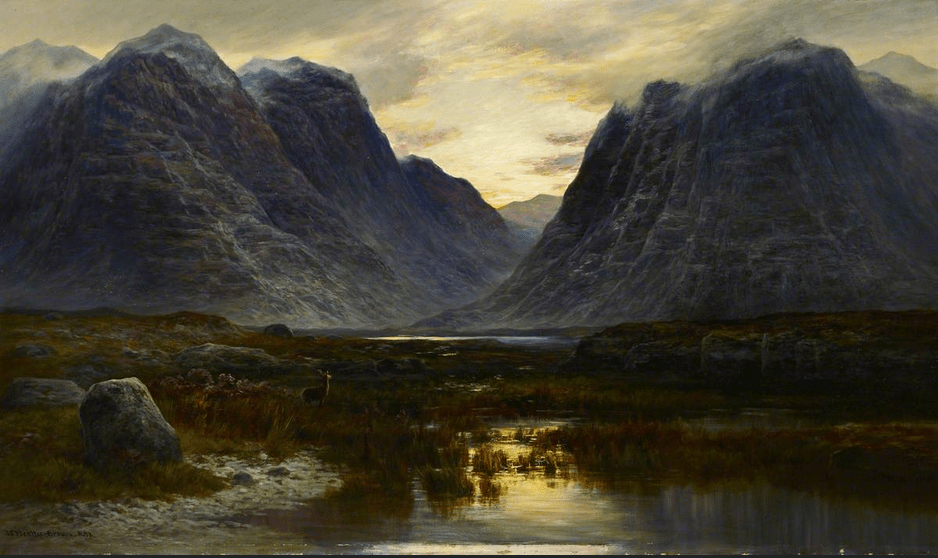

With that point in mind, we attempt to begin our narrative at the end of the last Ice Age. As temperatures rose, new topography emerged from beneath the melting sheets of ice. This newly formed landscape is one that we now recognise as modern Scotland, with its ice-carved bulwarks crowned in mantels of morning mist that pulsate with the deep purple hews emanating from the dew steeped heather. Hushed glens blanketed with cavernous expanses of ancient forests with galleries painted in golden hues. Rushing through the valley floor, brawl waters race to their lands’ end teaming with dark eddies that inspire reflections of a distorted otherworld beneath the rusty currents.

When the ice melted for a few months each summer, the tundra glens and plains of Scotland blossomed with edible vegetation that attracted herds of fauna from the south seeking fresh pasture. Following the herds north were their predators; chief among them were human bands of pioneers who had entered a new landscape. These bold and enterprising people began to understand that the world was slowly changing. Such events are the distant beginnings of the saga of the Picts, yet if there existed hunter-gatherer communities within the glens of Scotland before the last Ice Age, then the glaciers had ground away all trace of them.

Nevertheless, these first pioneers who came north have no myths or oral traditions that survive to give them a name other than their elaborate burials. Nevertheless, these anonymous peoples began the saga of Scotland, and their successors offer up more compelling evidence of their existence as they approach us more closely in time. These peoples are ancestors of the modern Celts, and they were the silent builders of great monuments. The legacy of these peoples is transmitted though time in the solemn monuments they left behind; the standing stones at Callanish on the Isle of Lewis, the Ring of Brodgar, and Stenness on Orkney. These people were to become the valiant warriors worthy of note by their enemies as they strived to preserve their way of life against the disciplined ranks of hardboiled Roman Legions at the Battle of Mons Graupius and the sculptors who carved the remarkable symbol stones that grace Scotland’s glens.

Over eight thousand years, these noble peoples attempt to tell us their story, but they were not Scots in the modern sense. Accordingly, their exceptionally long experience within Scotland’s landscape is often dismissed as prehistory or a preliminary precursor to real history. In other words, scholars have often neglected this portion of Scottish history for the comforting chronological rhythm of confirmable dates, kings, and battles that began with the trifling Kingdom of the Scots (Dál Riata) in the 9th century. Naturally, Scotland’s history is much more vibrant than such shallow inquiries. Given the fact that the earliest evidence of human occupation in Scotland, found on the Rims of Isla, has been dated to around 10,800 BC.[1]

Setting aside the fascinating pre-history of Scotland, we must refocus on the origins of the sculptors of the ornately carved cross-slab that is the centrepiece of this inquiry. Nevertheless, it is critical to understand that we are forced to rely on accounts written by the would-be conquers of Pictish peoples in order to formulate our suppositions. Writing in 297 AD, the Roman commentator Eumenius was the first to label these diverse people as the Picts.[2] Their Roman opponents branded these fierce peoples, the Picti, which translates to the painted or tattooed ones. The Latin word might be a translation of some form of Pecht, which is the old Welsh word for the ancestors.[3] While Eumenius gave the tribes of North of Hadrian’s Wall their historical name, he was not the only Roman writer to mention these intense people.

In 98 AD, Tacitus penned the Agricola in honour of his father in law’s triumphant defeat of the Caledonii. Like most written account of the Picts, Tacitus’s chronicle contains severe limitation because of his civic fides and pietas, as well as his filial piety to his father-in-law Agricola, which contaminate the narrative. Nonetheless, Tacitus supporters maintain that his devotion to Agricola should be pardoned and that such notions do not discredit the textual information concerning the Picts. Regardless, Tacitus writes ambiguously, and the Agricola is a general narrative, rather than providing a detailed account of Agricola’s life. Despite these constraints, Tacitus pens a tale that is probably accurate from the perspective of a Roman citizen of Gaulish ancestry. Although pro-Roman, the narrative undoubtedly curries favour with Agricola and is laced with Tacitus’s moralistic conception of traditional Roman values.[4] With that said, Tacitus’s account gives us one insight into these mysterious peoples, the martial nature of their society. Tacitus’s account of the Caledonii’s military tactics do match up with accounts of other earlier Roman writers[5] and from this one can conclude that specific tactics were standard for the tribal peoples of the British Isles. Apart from military information, Tacitus gives us a little insight into the daily lives and culture of the Pictish tribes.

From the archaeological evidence, we know that the Picts lived in tightly knit groups and built their roundhouses out of wood. However, in some areas, they built stone brochs and designed numerous standing stones with sophisticated twisting carvings. An important point to note is that the Picts spoke an Insular Celtic (P) language,[6] which differed from the language of the recently arrived immigrants from Northern Ireland, the Scots. These small communities were made up of families belonging to a single clan that was presided over by a tribal chief, who was chosen by the community for their perceived prowess as a warrior and/or wisdom.The majority of the time, these clans acted in their own interests, and small-scale cattle raids were a central part of clan life. When fighting in these skirmishes or against other clans, they do so in small bands called Fianna. A fiann was a war party that comprised of landless young men and women of partial noble stock.[7] However, the various clans often banded together when threatened by a common enemy and elected a single chief to lead the coalition, such as Tacitus’s Galgacus demonstrates.

Despite Rome’s best efforts to militarily subdue the northern tribes, by 200 AD, the Picts had been forged into a loose political confederation and had become a force not to be reckoned without due caution. Commencing in 184 AD, northern tribes began a steady effort to overrun the northern frontier of the Roman Empire (present-day Yorkshire, England) and on more than one occasion defeated the Roman garrison stationed along Hadrian’s Wall.[8] These raids and counter Roman incursions into Scotland had a unifying effect upon the Picts and served to re-enforce the warrior ethos within the society. Another effect of Roman contact was that they began to form cohesive groups based on kinship and the leading persons within these groups became the heads of the kindred. Eventually, this system evolved into the idea that there should be chief amongst chiefs (Ard-ri) to unify the tribes under a leader who was a descendant of a common ancestor. However, they were not kings in the Continental sense. Instead, they were leading warriors chosen for their martial prowess and a shared descent from a common ancestor.[9]

Over the next 600 years, this loose confederation of tribes developed into an organised and robust political coalition. The Picts had established a sophisticated society, which produced an abundance of artwork ranging from finely crafted metal and jewellery, to beautifully carved stone sculptures. Even with these social changes the system of kin-based leadership would continue until the seventeenth century and plays a prominent role in the spread of Christianity during the late eighth and ninth centuries when The Cadboll Stone is thought to have been carved.

The Sacred Landscape

In order to understand the people who crafted The Cadboll Stone, one needs to comprehend their pre-Christian religious practices, as they are currently understood. Even though the Picts spoke a different language from their Q-Celtic cousins, they seemed to have shared similar religious beliefs with other Celtic peoples. Trying to understand their religious practices is a bit like trying to piece together the details of Christian worship by only looking at the ruins of their cathedrals. Thus, it is impossible to do anything other than to make informed conjectures about the nature of Pictish spirituality. With this in mind, they seem to have worshipped a Mother Goddess figure, similar to the Q-Celtic (Gaelic) figure of Cailleach. In Old Gaelic, Cailleach means vailed one, a wise old woman, who ushers in winter with her féileadh mòr.[10] The goddess was the architect of landscapes, and her worship was centred on Paps or Ciochs (Gaelic word for breast), which are prominent geophysical landmarks thought to be representations of the goddess.[11] At hilltops like Cairnpapple, worshipers brought sacrificial woods (hazel and oak), and in 6 hearths around the summit, they set alight fires as an offering. Pieces of pottery and axes were also deposited around the flames as sacrifices to the goddess.[12] The significance of these offerings is unknown, but the sheer volume of these hilltop ritual sites demonstrates that the worship of a mother goddess was commonplace in North Britain, as well as Ireland and Wales.

Other ritual locations were henges, stone circles, sacred wells or bodies of water, which are theorised to be places where the spirit plain intersected with the world of man.[13] These bodies of water became centres of ritual sacrifice, where objects, and humans were offered up to the gods. The objects were items of great worth, such as a sword, shield, or cauldron. However, the items were deliberately mangled before being sacrificed to the gods. Other items include precious metals, and models of limbs or other parts of the body, which had been injured or where in need of healing. In addition to material offerings, at times Celtic peoples would offer human sacrifices. Though a rarity, human sacrifices were such an extreme offering that was only performed during times of great social unrest. When human sacrifice was conducted, the person would be ritually sacrificed using what the Irish Annals term the “threefold death.” The threefold death is when a person is killed instantaneously in different three ways: garrotting, the cutting of the throat, and drowning. While these deaths may seem brutal, it is essential to note that the victims of these acts of violence seem to have been of high social rank, and even willing.[14] This point about the status is a key archaeological insight that calls into question Roman accounts of the commonality and callousness of human sacrifice with Celtic society.[15]

Such rituals were a part of the very essence of Pictish society because their lives were very elemental. In other words, they were closely linked to the land, the sky, and to the bodies of water that coursed through their lives, which had been virtually unchanged by the hand of humanity. Hence, one is left with a strong sense of a ritualised relationship with the landscape, something directed by a higher authority. This fact can be observed when one considers the Bronze Age societies had an umbilical relationship with the land around them that is no longer felt in our time. The land allowed the Pictish culture to thrive; they hunted and harvested its natural bounty, all the while planting their ancestors inside the very same ground. Such burials, whether cremated or entombed, were central to Pictish notions of the afterlife. This core concept can be seen in the archaeology when one observes the care that these people took in depositing their dead and the placement of grave goods with the deceased. Tombs, especially, seem to have functioned as a sort of dream chamber where the dead were “absorbed into the communal identity.”[16] Indeed, such was the closeness of these people with the dead that they may have interacted with them at certain times of the year. Even with the continual changes in ritual practices, many sites across Scotland are merely reconditioned to suit the new beliefs, while still preserving the sacredness of the older interments.[17] That being said, all these assertions are purely conjecture based on inferences from other cultures. The truth about which deities the Picts worshipped and what they thought about an afterlife will never be known.

The introduction of Christianity into Pictland in the sixth and seventh centuries brought with its distinctive norms and ritual customs that were to affect Pictish society significantly. The new religion brought innovative concepts of monotheism and an omnipotent male sky god. Additionally, these missionaries introduced the idea of original sin and that women, in particular, were sinful. Such notions would have profoundly changed their society wherein, written and archaeological evidence suggests, women were equal to men and their primary deity was a female goddess, who could be found within the landscape. Such sweeping changes to Pictish society, gradual as they were, meant that they were forced to modify their perceptions of themselves and the landscape they inhabited.[18]

The Monks Arrive

St. Colmcille (Columba) is usually recognised as the main missionary who first converted the northern Picts to Celtic Christianity. In 563 AD, Colmcille established the monastery on Iona in the territory of Scots Kingdom of Dál Riata. Two years later, Colmcille journeyed to the Inverness area to meet the newly crowned Pictish chieftain of Fortriu, Brude mac Maelchon (r. 565–585 AD). Once at Bridei’s court Colmcille clashes with a chieftain’s druid, who prevented his entrance. But Colmcille defeats the druid with a divine wind and gains entrance into the stronghold.[19] There are conflicting accounts about Bridei’s reaction to Colmcille; Bede recounts that he was converted after the druid is defeated, but Colmcille’s biographer, Naomh Adhamhnán (Adamnán of Iona), notes that the Colmcille was well received. However, it is also conceivable that Bridei was already a Christian in the tradition brought to Pictland by St. Ninian. In the early 400 AD, St. Ninian is said to have established a Christian centre at Whithorn in southwest Scotland, where he constructed a missionary and converted southern Pictish tribes. While there is evidence of Christian occupation at Whithorn, there is no further indication of the spread of Christianity northwards. Colmcille’s role in converting the Picts could possibly be exaggerated, yet it is accurate to say that by the early 700 AD Pictland was principally converted to Celtic Christianity, except that God’s Word did not entirely spread from Iona.[20]

As aforementioned, the Picts are presumed to have been the descendants of a loose confederation of tribes known as the Caledonii, as well as sixteen other tribes who were mentioned by Roman commentators Tacitus, Ptolemy, Eumenius, and Constantius Chlorus.[21] While Roman sources mention these various tribes, it is hard to pinpoint where each tribe’s territory within Pictland was located. However, the works of The Venerable Bede in his Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum, and the Annals of Ulster, historians know the specific names and locations of seven Pictish kingdoms, as well as some of the early Pictish rulers.[22] Indeed, from the list of kings, we can discern who might have commissioned The Hilton of Cadboll Stone and its apparent purpose. The Cadboll Stone’s chronicle began during the eighth century when the Pictish King Nechtan attempted to bring his kingdom firmly into the mainstream by mandating that his people follow the Roman tradition of Christianity. In doing so, Nechtan was linking Pictland, to shared experiences, through Northumbria, with the Continent. Pushing his influence north, Nechtan may have sent Northumbria delegates to north Pictland (present-day Inverness-shire and Ross-shire), where a Columbán Monastery centred at Rosemarkie near Hilton of Cadboll, whose abbot Curetán was supportive of the Roman position.[23] Indeed, the extraordinary wealth of eighth and ninth century Pictish Christian sculpture in Eastern Ross and the Black Isle may stem from this restructuring of Christianity.

In the early 700 AD, Abbot Ceolfrith of the monastery from the Monkwearmouth–Jarrow Abbey in Northumbria convinced the Pictish King Nechtan mac Der-Ilei (r. 706-729 AD) to follow the Roman Catholic tradition and to reject Colm Cille’s Celtic Church. Interestingly, Abbot Ceolfrith was the ward of a young the Bede, the quasi-historian from whom the majority of our historical knowledge on these obscure events are based. Nevertheless, King Nechtan was weak from his recent defeat at the hands of the Northumbrian King Osred sent an offer of peace through Ceolfird. In return Ceolfird sent Anglo-Saxon artisans to build a Roman-style church that was to be dedicated to Saint Peter; the location of the church is unknown. Declaring his support for Rome, Nechtan expelled all of Colm Cille’s monks and clergy associated with the Insular Church (Celtic), who would not adopt the Roman tradition in the year 717 AD. Nechtan’s well placed Roman adherent allies Ecgberht of Ripon, who had assumed the influential position of Abbot of Iona in 712 AD, and Curetán of Rosemarkie began to weed out dissenters through patronage. [24]

Despite the apparent acceptance of Nechtan’s Romano-Northumbrian decree, many within Pictland saw his act as a deliberate betrayal of Pictish sovereignty and a subversion of their religious traditions, as well as their culture. Nechtan’s submission to Northumbrian overtures and his imposition of Roman reforms within the Insular Church sent sparks throughout the Kingdom, which kindled the fires of political instability and rebellion that would lead to the loss of his throne. Yet, for some unknown reason, Nechtan abdicated in 724, then entered a monastery, leaving the throne to his nephew, Drest. Perhaps, Nechtan was a religious zealot, as Bede recounts. Regardless, two years later, in 726, Drest had Nechtan imprisoned but was freed after Drest was defeated in battle by yet another rival, called Ailpín. Instead of returning to monastic life, Nechtan fought the remaining rivals with the backing of Northumbria until 729 when he was defeated at the battle of Monith Carno at the hands of Óengus mac Fergusa. From this point on Nechtan the Philosopher King or Romanist stooge fades from the pages of history.[25] Despite, Nechtan’s dynastic failures, his religious machinations would emit profound echoes across the last remnants of the Celtic culture and foretell the being of the end for the distinctive Insular Church.

The religious rift and subsequent social upheavals within Pictland has its origins within the controversy over Easter and the manner of tonsure[26] with the Insular Church, which was determined by the temporal power of King Ōswīg of Northumbria (r. 612-670AD) at Synod of Whitby, 664 AD. At stake was more than the date of Easter. The Insular Church had developed distinctive doctrinal differences that reflected cultural adaptations incorporated from Celtic society, akin to the variations the arose in the Eastern Orthodox Church. The teaching of Christ and the Word of God remained unaltered, the Insular Church’s only disparities with Rome occurred in non-scriptural doctrine and practice. What was distinctive was the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople had political patronage of the Roman Emperor. Thus, the Eastern Church could ignore the consolidation and dictatorial edicts from an increasingly secular focused Roman Pontiff.

From the onset, the debates at Synod of Whitby were heated, and the Roman delegation held a tone of righteous indignation. The proponents of the Roman potion, Agilbert of West Saxon and Wilfred the abbot of Ripton, openly insulted Saint Colmcille. They called into question if he was even a Christian and he would be barred from Heaven. Representing the Insular Church was Colmán of Lindisfarne, who, from Bede’s account of the proceedings, put forth a rather confused and disorganised defence of Insular doctrines that failed to create a sense of gravitas within the mind of the King. At this point, the Roman delegation reminded King Ōswīg that Saint Peter was the rock upon which the church was built, and he controlled the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven. Once that realisation became apparent, King Ōswīg gave deference to the Roman doctrine on the grounds that he did not want to be on the wrong side of the man who controlled the gates. In a final twist of the imperial knife, Wilfred invokes the Council of Nicaea (325 AD) and the threat that those who reject its dictate were to be considered “accursed.”[27] What is troubling about the Council of Nicaea and the Synod of Whitby, from a spiritual standpoint is that both councils placed the ultimate authority to judge religious matters in the hands of a temporal power ruler. Moreover, in both cases, the respective rulers, Emperor Constantine (r. 306-337 AD) and King Ōswīg, were not men steeped in the theological study of the scriptures. With that point in mind, what is bewildering about these various councils is the idea that significant church doctrines would be decided by earthly rulers with little comprehension of the scriptures and that Christians continue to believe that the results of these temporal councils are the Word of God.[28]

Setting aside of the Roman Church’s tendency to place significant religious decisions into the hands of earthly rulers, the long term consequences of both the Synod of Whitby and imposition of Roman Catholic bishops to influential potions, such as the Roman adherent Ecgberht of Ripon being appointed the abbot of Iona, would eventually ensure the dominance of Rome’s increasingly temporal influence over the Insular (Celtic) Church. From the onset of Roman Papacy’s pursuit of the secular consolidation of power in the late 500 AD, Pope Georgy the Great, with the encouragement of temporal Anglo-Saxon rulers wishing to link their kingships with Rome, sent Augustine, a Benedictine prior of St. Andrew’s in Rome, to bring the Insular Church under the authority of the Papacy. Pope Georgy the Great’s secular and spiritual consolidation of power was justified on the grounds that since the Apostle Peter was chosen by Christ as the lead Apostle and he was the founder of the Roman church, it stood to reason that he was Peter’s successor.[29] This linkage to the Apostle Peter implied that Pope Georgy, as well as his emissaries, had the authority to judge on certain moral and church doctrinal issues, despite the lack of scriptural justification for his assertions.

When the Insular church leaders learned that the Roman Pontiff had sent a representative to call them to heel, they sought advice from a revered pious hermit, who told them that if Augustine stood to honour their arrival, he was a humble man embodying teachings of Christ and they should remain to hear what he had to say. If he sat, however, he was a prideful man and did not emulate Christ, which meant that they should ignore his prideful words.[30] Indeed, Augustine’s contempt for the cultural adaptations within the Insular Church originated with the Roman Catholic sense of superiority that led them to view the Insular Church’s followers as heretics or schismatic at the very least, thus there were far-deeper doctrinal differences that separated the two church traditions.[31]

The Celts were an independent people that wished to remain so in many ways, not in the least, in their desire to worship God according to the scriptural teaching of the Apostle John, as was brought to them by missionaries in the early fifth century, which sparked the Age of Saints. Indeed, the very idea of a God sacrificing his only son in order to save the peoples of the world profoundly resonated with Celts given the practices of their native religion, which placed significant importance in forfeiting up to the gods’ items and people of great social value in order to maintain stability within society.[32]

Accordingly, Christianity’s development within Celtic lands acquired a less theocratic tradition that incorporated the native people’s reverence for the landscape. In the name of God, Christian saints rapidly converted pagan ritual sites into places of Christian worship. These early missionaries infused into the foundations of the Insular Church the importance of dedication to His Word through monastic prayer within daily life, developing personal relationships with God, and the importance of good works within the community.[33] Such practices stand in stark contrast to Rome’s theocratic musings that were increasingly temporal and intolerant in nature. These statist tendencies within the Roman Catholic church’s hegemony on the interpretation of the New Testament within the Western Christianity would culminate to set Europe ablaze with the pyres of commended heretics and stain God’s Word in the blood-soaked torture chambers of the inquisition by the eleventh century.[34]

Accordingly, the consequence of the Synod of Whitby is often disregarded as a mere debate over the date of Easter because the Roman church was an influential political power with increasing monetary resources. The Roman church’s blessing could offer legitimacy to kings, and in return, kings created lands for the church tax. Equally, no religious centre could endure without royal or aristocratic patronage. Accordingly, Roman Christianity spread through the top of Pictish society with the conversion of the aristocracy and then its dissemination to the lower rungs by way of achieving political favour at court. Methodically, from the top, the Roman church gained influence over the common clergy, monks, and laypersons, which eventually crushed the native Celtic adaptations to Christianity. Along with doctrinal dogmas, Rome imposed its view of women and their subvariant place within society, which has limited scriptural foundation given the teachings of Christ. Thus, ending the age-old custom of flexible social roles within the Celtic societies of the British Isles.[35] Ironically, the Synod of Whitby was held at the Abbey of Whitby in Yorkshire, and the head of the abbey was a woman named Hilda of Whitby. Hilda was the abbess of a monastic community comprised of both men and women. The synods result would eventually bar women, like Hilda, from holding high positions within the church.[36] Such is the significant and enduring consequences of the Synod of Whitby.

The Hilton Of Cadboll Stone

Leaving behind the debate surrounding the consequences of the Synod of Whitby, The Cadboll Stone was created during this volatile period when traditional Celtic beliefs were still interwoven within Christianity, and Rome’s influence had not reached the wilds of Scotland’s windswept northern coast. The stone, therefore, is a beautiful blend of traditional Pictish and Christian symbols. From the imagery, one can discern that the local community is in a transition period. Additionally, the monument displays the distinctive rectangular shape and large cross relief of a Class II symbol stone, which bears some resemblances of stones found in Northumbria. The central panel’s scene vividly illustrates the notion that Christian beliefs were becoming common place and were supplanting traditional pagan concepts.[37] As mentioned in the previous section, Christianity did not merely influence the spiritual and artistic life of the Picts. Rather a hybridization occurred. The monument is a prime example of this spiritual transformation and was carved at some point around 800 AD. The monument once stood on the East coast of the Tarbat Peninsula in Ross-shire. Lamentably, the elaborate cross on the reverse side was defaced when the stone was repurposed as a headstone and substituted with an inscription of a presumed local person, “Alexander Duff, and his three wives.”[38] Hints of the cross’s ornate design can be observed on the remnants of the cross slab’s base. Mercifully, the unmarred face of the stone endured the passage of time with its Pictish reliefs relatively unspoiled.

The stone’s front panel has an upper margin of acanthus, or vine scroll, populated by stylized winged creatures. In the bottom margin, one observes triskelions, a Celtic design consisting of three interlocked spirals. Within the margin are three rectangular panels located in the centre of the stone relief. The central top part of the margin is adorned with decorative forms of Pictish symbols of the double-disc and Z-rod. This ornate double disc and Z-rod might denote lineage or status within Pictish society.[39] Preceding the double-disc and Z-rod section of the stone, there are the Pictish symbols of crescent V-rod and a double-disc; again these symbols may reflect lineage, status, or marriage. Continuing down the stone, the central panel reveals an astonishing hunting scene, in which one of the principal figures is a distinctly portrayed female figure. One does note the special care that was taken to add detail to the carving of this figure’s robes and long flowing hair. It is clear that the central relief is purposefully attempting to distinguish this figure as a woman and not like the other male figures. Additionally, this woman is depicted wearing or holding a great brooch of penannular style, a type of brooch which fastens clothes and is often large with ornate decorations. She rides the horse side-saddle. The large penannular brooch, such as the Hunterston Brooch, highlights how intricate and prestigious these objects were within Pictish society. To the right of the woman are two trumpeters on foot, dressed in traditional Pictish clothing. Behind the noblewoman is another rider and in the foreground are horsemen and hounds hunting for deer. A mirror and comb are located in the top left-hand corner of the panel, traditional items of the fairer sex. It is important to note that the hunting scene may merely illustrate the gentle lifestyle of the aristocracy of Pictish society who commissioned this stone, though it could have unknown Christian implications such as an allegory about conversion or the salvation of the soul.[40] Accordingly, the reader should understand that the true meaning of all the imagery and symbols on these stones are, as of yet, unidentified by scholars.

With that said, The Hilton of Cadboll Stone appears to be drawing on Christian imagery and emphasising the importance of the female rider, which might be the Virgin Mary or even Jesus, both of whom have been previously depicted riding side-saddle. This notion is further advanced by the fact that the defaced side of the stone has long been assumed to display a cross, and the recently excavated lower section revealed a base of a Celtic cross.[41] With this in mind, The Hilton of Cadboll Stone, The Nigg Stone and The Shandwick Stone on the Easter Ross peninsula are currently regarded as an interrelated sequence, representing a particular ‘school of sculpture,’ probably connected to the monastic settlement at Tarbat known as Portmahomack.[42] A considerable quantity of Pictish sculpture has been found through excavations at Trabat, which lends credibility to this assumption. These recent discoveries at Portmahomack, share similar characteristics in craftsmanship and style with the monuments on the Easter Ross peninsula. Furthermore, the proximity of the stone’s locations with the monastery or religious centre at Portmahomack also facilitates the aforementioned ‘school of sculpture’ theory. Taken with the pieces of evidence mentioned above, it has been argued that the Pictish culture in Easter Ross during the eight and 9th centuries was made up of small wealthy estates, whose lairds are thought to have commissioned the cross-slab monuments. [43]

Subsequently, there are two leading theories as to the purpose of the stone. The first theory put forth by historian H. James, argues that the stone is a memorial for one of three dead Norse princes from within the King’s Sons folk legend,[44] which links the Hilton, Nigg, and Shandwick cross-slabs together in a localised narrative. While this theory fits reasonably into a set frame of the local tradition, it begs the question as to why would the Picts take the time to sculpt Christian memorials for pagan Norse princes, who were sent there to attack the Pictish tribes residing in the area? Moreover, when considering the fact that within the King’s Sons folk legend the Pictish noblemen lead these Norse princes to their deaths, it brands James’s theory as contradictory at best.[45]

What is exceptional about the Hilton stone, apart from its exquisite symbols and motifs, is to see a woman prominently portrayed in a central position of a Pictish stone. This obvious portrayal of a woman is significant because, apart from the mirror and comb, there are no other depictions of a clearly identifiable female figure on any other stones. Thus, the second theory put forth by historians T. Clarkson, W. Cummins, and R. Sansom, suggests this portrayal signifies that the figure is possibly a female Pictish leader of some notable authority and wealth. The mirror and comb are theorised to be Pictish symbols traditionally associated with women.

The historians mentioned above suggest that the comb and mirror could symbolise Pictish denotation for a female. Hence, the presence of the comb and mirror symbol on a Pictish stone might symbolise the gender of the person, who commissioned the stone or was commemorated. Furthermore, these historians propose such imagery suggests that women in Pictish society could obtain high status, considering the high proportion of symbol stones bearing the symbols of a comb and mirror. In Sansom’s survey of Pictish stones, 20 per cent of the stones examined contain the comb and mirror symbols either in combination or one and not the other.[46] An example of another stone containing a comb and mirror is The Aberlemno Serpent Stone, which shows the very common arrangement of two symbols above a comb and mirror. The top symbol is recognisable as a serpent, the one in the middle is an abstract design looking like a ‘Z’ combined with a pair of discs, and at the bottom is a round hand-mirror next to a small comb. Another example is The Dunnichen Stone, which has three symbols, a mirror, and comb, a rare depiction of a flower, a double-disc, and Z-rod.

As on Hilton, the mirror and a comb are found in various combinations with other symbols, most notably with the double-disc and Z-rod. Historian W. Cummins theorises that the double-disc and Z-rod could be the symbol for the royal house of Drust or Drosten and the crescent and V-rod may be the symbol for the royal house of Brude. It is interesting to note that these symbols are only found on other stones, all of which are located to the south in County Angus near the heart of ancient Pictish capital of Scone (present-day Perth). The Venerable Bede further advances this possible correlation of female figure as a powerful leader descended from two royal houses in his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, where he writes that Pictish royal succession was partially determined through the matrilineal line.[47] Thus, this central panel on the Hilton stone lends validity to traditional legends that talk of the prominence of certain female figures, as in The Saga of Triduana and the Irish Annals.[48] Consequently, the Hilton stone might be a border marker that indicates that the local chieftain was a woman of royal lineage, who had converted to Christianity.

The reader should also consider that with recent advances in archaeology, it has been discovered that 10 per cent of all female Celtic burials contain weaponry and the skeletal remains bare the signs of battle.[49] Additionally, there are known references in early Irish writings, such as in The Annals of Ulster or The Book of the Deer, to female leaders,[50] which suggest that women warriors and leaders were common among Celtic peoples. It is known that in Ireland, women were members of the Fianna and wealthy landed women were required by law[51] to bear arms, as well as to have the skills to employ those weapons.[52] It can be understood from these Irish sources, that Pictish culture held similar beliefs and practices. Moreover, there are also known historical figures to which some historians have pointed to as further evidence of the commonality of female leadership throughout the Celtic world. Celtic warrior queens like Macha Mong Ruadh, Méabh of Connaught, Creidne the Feinid, and Cartimandua. Each of these women is worthy of further mention but one stands apart from the rest, Buddug (Boudicca). Boudicca was the queen of the British Icenitribe, who in 60 AD lead a largely successful rebellion against the Romans in southern Britain in response to the Roman assault on the Druidic holy site of Isle of Anglesey that killed an estimated 80,000 Romans and their British allies.[53] Boudicca commanded a tribal army of 100,000 independent warriors, which was no small feat when considering that she had to convince other male leaders from other tribes like the Trinovantes to join in the revolt.[54]

Additional evidence that supports women’s fluid social roles in Pictish society can be found in the Cáin Adamnáin or Lex Innocentium (Law of the Innocents).[55] Legend has it that during the aftermath of a battle between the Picts and the Northumbrians, possibly the battle of Dunnichenin 685 AD, Adamnán of Iona and his mother were surveying the bloody field of carnage when they came across a slain female Pictish warrior with an infant still clinging to her breast. The Abbot’s mother was so distressed by this tragic scene that she proposed to Adamnán the philosophies behind The Law of the Innocents. The Abbot’s new law forbade the killing of children, clerics, clerical students, and peasants on clerical lands. Additionally, the law forbade rape and made it illegal to dispute the chastity of a noblewoman. But more importantly, the law prohibited women from fighting in combat or to command independent warrior bands (Fianna). To enforce this new law, Adomnán managed to get King Ferchar Fota of Dál Riata, King Taran of Pictland, fifty one Irish chieftains, and forty high ranking members of the clergy to agree to ratify the Law of the Innocents in 697 AD.[56] Recall, that Adamnán enjoyed the patronage of the Kings of Northumbria and that Abbot Ceolfrith seems to have convinced him of the correctness of the Roman position; according to Bede. Adomnán’s conversion to the Roman Catholic tradition inherited Pagan Rome’s ideas about the proper social status of women. Yet, as abbot of Iona, Adamnán’s decree seems to have been accepted by the secular powers but challenged by the Insular Church leaders, which led to a schism on Iona. This open rejection of Adamnán’s conversion led to him leaving the sacred island to seek out allies in monasteries in Ireland.[57]

As the reader can gather from the various pieces of evidence mentioned above, The Hilton of Cadboll Stone is quite possibly a border marker that indicates the wealth of a local female chieftain with royal lineage, who desired to communicate a Christian message. Moreover, the stone is further archaeological proof that women held more fluid social roles within Pictish/Celtic societies than previously acknowledged by historians. The reader should be aware of the fact that until the late 20th century, the Picts were portrayed in scholarly, as well as in popular literature as insignificant, obscure, and a painted ‘race’ that lived a life of barbarism.[58] Consequently, the captivating depictions on the central panel of The Hilton of Cadboll Stone stand in stark contrast to previously held notions of the Pictish society. In the past historians like F. Wainwright, writing in 1955, have emphasised the role of the “King” or “Husband” figure in the hunting scene and minimised the significance of the prominently displayed female figure.[59] What past historians have failed to recognise, is that the Pictish peoples had their own social constructs that had yet to be completely altered by the doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church. Appropriately, The Hilton of Cadboll Stone serves as a notable symbol of a period when the old pagan social norms and the new Christian doctrines began to intermingle in North Pictland.

In contrast to past views of Pictish society, today these noble peoples are represented in archaeological publications, as a ‘perfectly respectable’ population, with both men and women having a relatively equal social status. Though Celtic society was by no means utopian, with rampant tribal warfare, Viking invasions that plagued the coast, and endemic slavery. Nevertheless, by the seventh century, the Picts had entered the mainstream of European art and civilisation. The Picts’ social and political organisation began to mirror developments taking place elsewhere in Europe.[60] In characterising the Picts, historian A. Ritchie explains that the Picts “were farmers, horse-breeders, fishermen, and craftsmen, but above all, they were warriors and theirs was an heroic society.”[61] Accordingly, Pictish stones such as The Hilton of Cadboll Stone, are seen as representing the wealth, prestige, and Christian beliefs of the Pictish aristocracy, as well as the artistic skill of their anonymous stone-carvers.

The reader can appreciate from this concise investigation of The Hilton of Cadboll Stone, that there are no conclusive theories that completely explain or clarify the significances of the intricately carved symbols that adorn Pictish stones, which solemnly dot the Scottish landscape. Thus, for the moment, it seems that the Pictish people will continue to retain some of their secrets. With the passage of time fresh and exciting revelations will be brought to the surface, which will bring us closer to an understanding of these fascinating peoples. In the meantime, one can still marvel and appreciate the artistry of a culture that thrived almost 3,000 years ago.

Bibliography

Adamnan of Iona. Life of St Columba. Translated by Richard Sharpe. London, UK: Penguin, 2005.

Aldhouse-Green, Miranda J. Dying for the Gods: Human Sacrifice in Iron Age & Roman Europe. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: History Press, 2014.

Barclay, Gordon J. “Cairnpapple Revisited: 1948–1998.” Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 65 (1999): 17-46.

Caesar, Julius. Caesar: The Gallic War. Translated by H. J. Edwards. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

Clarkson, Tim. The Picts a History. Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2012.

Crawford, B. E. Conversion and Christianity in the North Sea World. St. Andrews, Scotland, UK: Committee for Dark Age Studies, University of St. Andrews, 1998.

Cummins, W. A. The Age of the Picts. Far Thrupp, Gloucestershire: A. Sutton Pub., 1995.

Crualaoich Gearóid Ó. The Book of the Cailleach: Stories of the Wise-Woman Healer. Cork, IRL: Cork University Press, 2015.

D’Ambrosio, Marcellino. When the Church Was Young: Voices of the Early Fathers. Cincinnati, OH: Servant Books, 2014.

Deane, Jennifer Kolpacoff. A History of Medieval Heresy and Inquisition. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2011.

Edwards, Thomas. After Rome, 400-800CE. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Green, Miranda J. Dying for the Gods: Human Sacrifice in Iron Age & Roman Europe. Stroud: Tempus, 2001.

Gies, Frances, and Joseph Gies. Women in the Middle Ages. New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 1978.

Hardinge, Leslie. The Celtic Church in Britain. London, UK: S.P.C.K. for the Church Historical Society, 1973.

Heaney, Marie. Over the Nine Waves: A Book of Irish Legends. London: Faber and Faber, 1994.

Henderson, George, and Isabel Henderson. Art of the Picts: sculpture and metalwork in early medieval Scotland. New York, N.Y.: Thames & Hudson, 2004.

Herren, Michael W., and Shirley Ann. Brown. Christ in Celtic Christianity: Britain and Ireland from the Fifth to the Tenth Century. Suffolk, UK: Boydell and Brewer Press, 2002.

Hudson, Benjamin T. The Picts. Edinburgh: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014.

James, Heather F. A fragmented masterpiece: recovering the biography of the Hilton of Cadboll Pictish cross-slab. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 2008.

Kateusz, Ally. Mary and Early Christian Women: Hidden Leadership. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

Maxwell, Gordon S. A Battle Lost: Romans and Caledonians at Mons Graupius. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1990.

McHardy, Stuart. Tales of the Picts. Edinburgh: Luath Press, 2005.

Moffat, Alistair. Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History. London, UK: Thames & Hudson, 2005.

–– The Faded Map: Lost Kingdoms of Scotland. Edinburgh, UK: Birllinn Limited, 2014.

O’Donovan, John, Eugene O’Curry, W. Neilson Hancock, Thaddeus O’Mahony, A. G. Richey, W. M. Hennessy, and R. Atkinson, trans. Ancient Laws of Ireland and Certain Other Brehon Law Tracts. Dublin, UK: Printed for His Majesty’s Stationer’s Office Published by A. Thomas, 1865.

Osiek, Carolyn, Margaret Y. MacDonald, and Janet H. Tulloch. A Women’s Place: House Churches in Earliest Christianity. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2005.

Oxenham, Helen. Perceptions of Femininity in Early Irish Society. Suffolk, UK: The Boydell Press, 2017.

Ritchie, Anna. Perceptions of the Picts: From Eumenius to John Buchan. Rosemarkie: Groam House Museum Trust, 1994.

Roy, James Charles. Islands of Storm. 1st ed. Dublin: Dufour Editions, 1991.

Sansom, R., and W. Cummins. “The Status of Women in Pictish Society.” British Archaeology 1357-4442, no. 3 (1995). Accessed January 1, 2014. http://www.britisharchaeology.org/.

Scott, Douglas. The stones of the Pictish peninsulas of Easter Ross and the Black Isle. Edinburgh: The Historic Hilton Trust, 2004.

Scherman, Katharine. The Flowering of Ireland: Saints, Scholars, and Kings. Boston, MA: Little Brown & Company, 1981.

Stephanus, Eddius. Life of Bishop Wilfrid. Translated by Bertram Colgrave. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Stokes, Whitley, trans. The Annals of Tigernach. Felinfach, Lampeter, Dyfed, IRL: Llanerch Publishers, 1993.

Tacitus, Cornelius. Annals and Histories. London: Everyman’s Library, 2006.

Torjesen, Karen Jo. When Women Were Priests: Women’s Leadership in the Early Church and the Scandal of Their Subordination in the Rise of Christianity. New York, NY: Harpercollins, 1993.

Wacher, J. S. Roman Britain. 3rd ed. Sparkford, Somerse: Sutton, 1998 Wainwright, F. T. The problem of the Picts. Edinburgh: Nelson, 1955.

Appendix A

P-Celtic Language: A Subdivision of the Celtic languages of Celtic Gaul and Celtic Britain, as they share similar characteristics. Brythonic languages included Welsh, Cumbric, Cornish, and Breton. These were the languages of the Picts and the Britons. P-Celtic differs from Q-Celtic Goidelic languages, which included Manx, Scots and Irish Gaelic. The Dál Riatan Gaels (The Scots) spoke a Q-Celtic Goidelic language.

Class II Pictish cross-slab: Stones that are rectangular shape with a large Christian cross and Pictish symbols on either side of the stone. The symbols are carved in relief (Impression that the sculpted material has been raised above the background plane) and the Christian cross with its surroundings is filled with various Celtic designs. Class II stones date from the 8th and 9th Century’s, Common Era.

Hunterston Brooch: 700 CE, the Brooch is cast in silver, gold and set with pieces of amber, and decorated with interlaced animal bodies. These types of brooch are of a complex construction and are made with precious materials. Furthermore, these were symbols of prestige and denoted the station for the wearer. Similar brooches have been found at burial sites thought to be of royalty or persons of high status. For more information see The Hunterston Brooch and its Significance by Robert Stevenson.

Portmahomack: The monument comprises the buried remains of a Pictish monastic settlement, used from 6th to 8th centuries AD and later re-occupied. The monastery began around AD 550 and a layer of burning suggests that fire destroyed the monastic buildings by about the year AD 800. However, the site was re-occupied and continued to function as a place for metalworking and crop processing until at least the 10th century. It had a burial ground with cist and head-support burials, a stone church, at least four monumental stone crosses and metal workshops and early Christian books. Additionally, there are around 200 fragments with of Pictish motifs carved into the stone. Many of the fragments seem to have been intentionally broken apart and where found in a layer of burning suggesting that the monastic buildings were violently destroyed, possibly in a Viking raid, about the year 800. These fragments have made Portmahomack one of the major centres of Pictish art. Nineteen pieces were found in and around the churchyard before 1994 and the University of York, between 1994 and 2007, found the remainder during formal archaeological investigations. For more information see Portmahomack: Monastery of the Picts by Martin Carver.

King’s Sons: “In this age says the tradition, the Maormor of Ross was married to a daughter of the King of Denmark, but the King’s daughter proved to an adulterous and unkempt wife. The Maormor of Ross sent the princess back to her father in Denmark. Once their princess told falsehoods to her father, the King, about her treatment at the hands of the people of Ross. The King of Denmark filled out a fleet and army to avenge upon Ross the cruelties and shame afflicted the King’s family. Three of her brothers accompanied the expedition; but on nearing the Scottish coast, they observed the Maormor of Ross of waiting for them with a small fleet. The Maormor of Ross lured the Danish fleet into a reef where almost all the vessels of the fleet ither foundered or were driven ashore by Maormor’s forces, and the three princes were drowned. The ledge of rock at which this latter disaster is said to have taken place, still bears the name of the King’s Sons. The bodies of the princes, says the tradition, were interred, one at Shandwick, one at Hilton, and one at Nigg. For more information see Scenes and Legends of the North of Scotland by Hugh Miller.

Saga of Triduana: A story of Greek Christian women who accompanied bishop of Patras Greece, named Saint Regulus. It was Regulus who brought the bones of St. Andrew the Apostle to Scotland in 345 CE. According to the 16th-century Aberdeen Breviary, Triduana was born in the Greek city of Colosse, and travelled from Constantinople with Saint Rule, who brought the bones of Saint Andrew to Scotland in the 4th century CE. Triduana was said to be a pious woman and she settled at Rescobie near Forfar in Angus. But her beauty attracted the attentions of a Nectan, King of the Picts. To stall these unwanted attentions, Triduana tore out her own eyes and gave them to Nechtan. Due to her bravery Triduana became a revered holy woman, healer, and councillor to the Nobles. Triduana spent her later years in Restalrig, Lothian, where she healed the sick and blind. For more information see Tales of the Picts by Stuart McHardy.

Foot Notes

[1] Alistair Moffat, Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History. (London, UK: Thames & Hudson, 2005), 23-50.

[2] Stuart McHardy, A New History of the Picts. (Edinburgh: Luath Press, 2008), 176.

[3] McHardy, A New History of the Picts, 36.

[4] Gordon S. Maxwell, A Battle Lost: Romans and Caledonians at Mons Graupius. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1990), 84-7.

[5] Julius Caesar, Caesar: The Gallic War. Translated by H. J. Edwards. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), 113-15.

[6] See Appendix A.

[7] Heaney, Marie. Over the Nine Waves: A Book of Irish Legends. (London: Faber and Faber, 1994), 155-214.

[8] Wacher, J. S. “Warfare and Its Consequences.” In Roman Britain. (2000 ed. London: Dent, 1978), 18-56.

[9] McHardy, A New History of the Picts, 79-86.

[10] See., Gearóid Ó. Crualaoich, The Book of the Cailleach: Stories of the Wise-Woman Healer. (Cork, IRL: Cork University Press, 2015).

[11] Alistair Moffat, Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History. (London, UK: Thames & Hudson, 2005), 152-53.

[12] Gordon J. Barclay, “Cairnpapple Revisited: 1948–1998.” Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 65 (1999): 17-46.

[13] See., The Megalithic Portal to experience the vast standing stone monument disbursement map.

[14] See., Anne Ross, Pagan Celtic Britain: Studies in Iconography and Tradition. (London: Routledge & K. Paul, 1967).

[15] Miranda J. Aldhouse-Green, Dying for the Gods: Human Sacrifice in Iron Age & Roman Europe. (Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: History Press, 2014).

[16] Moffat, Before Scotland, 134.

[17] Moffat, Before Scotland, 95-148.

[18] McHardy, A New History of the Picts, 94.

[19] Adamnan of Iona. Life of St Columba. Translated by Richard Sharpe. (London, UK: Penguin, 2005) 31-32.

[20] Alistair Moffat. The Faded Map: Lost Kingdoms of Scotland. (Edinburgh, UK: Birllinn Limited, 2014) 107-09.

[21] Anna Ritchie. Perceptions of the Picts: From Eumenius to John Buchan. (Rosemarkie: Groam House Museum Trust, 1994).

[22] W. A. Cummins, The Age of the Picts. (Far Thrupp, Gloucestershire: A. Sutton Pub.,1995), 7-12.

[23] Cummins, The Age of the Picts 7-12.

[24] McHardy, A New History of the Picts, 107.

[25] Whitley Stokes, trans. The Annals of Tigernach. (Felinfach, Lampeter, Dyfed, UK: Llanerch Publishers, 1993).

[26] Tonsure is the manner in which monks clipped their hair as a symbol of their entrance into a religious order. Evidence does point to the possibility of druidic origin for the Celtic tonsure but also such pagan notions were used by proponents of the Roman Church’s style. For a more through discussion on the matter see: Daniel McCarthy, “On the Shape of the Insular Tonsure”, Celtica xxiv (2003), 140–67.

[27] Eddius Stephanus. Life of Bishop Wilfrid. Translated by Bertram Colgrave. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007) 21-23.

[28] Philip Jenkins. Jesus Wars: How Four Patriarchs, Three Queens, and Two Emperors Decided What Christians Would Believe for the Next 1,500 Years. (New York, NY: Harper One, 2011).

[29] Marcellino D’Ambrosio. When the Church Was Young: Voices of the Early Fathers. (Cincinnati, OH: Servant Books, 2014), 275-273.

[30] The Venerable Saint Bede. The Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation. (London, UK: J. M. Dent and Sons, Ltd., 1973) 137-139.

[31] Leslie Harding. The Celtic Church in Britain. (London, UK: S.P.C.K. for the Church Historical Society, 1973), 28.

[32] Michael W. Herren, and Shirley Ann. Brown. Christ in Celtic Christianity: Britain and Ireland from the Fifth to the Tenth Century. (Suffolk, UK: Boydell and Brewer Press, 2002).

[33] Katharine Scherman. The Flowering of Ireland: Saints, Scholars, and Kings. (Boston, MA: Little Brown & Company, 1981), 166.

[34] See., Jennifer Kolpacoff Deane. A History of Medieval Heresy and Inquisition. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2011).

[35] See., Karen Jo Torjesen. When Women Were Priests: Women’s Leadership in the Early Church and the Scandal of Their Subordination in the Rise of Christianity. (New York, NY: Harper Collins, 1993), Carolyn Osiek, Margaret Y. MacDonald, and Janet H. Tulloch. A Women’s Place: House Churches in Earliest Christianity. (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2005), & Ally Kateusz. Mary and Early Christian Women: Hidden Leadership. (London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

[36] Frances and Joseph Gies. Women in the Middle Ages. New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 1978.

[37] Crawford, Conversion and Christianity, 31.

[38] Cummins, The Age of the Picts, 125-127.

[39] Cummins, The Age of the Picts, 125-127.

[40] Heather F. James, A Fragmented Masterpiece: Recovering the Biography of the Hilton of Cadboll Pictish Cross-slab. (Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 2008), 27-37.

[41]George Henderson and Isabel Henderson, Art of the Picts: sculpture and metalwork in early medieval Scotland. (New York, N.Y.: Thames & Hudson, 2004).

[42] James, A Fragmented Masterpiece, 27-37.

[43] George and Isabel Henderson. Art of the Picts.

[44] King’s Sons Folktale,See Appendix B 5.

[45] James, A Fragmented Masterpiece, 27-37.

[46] R. Sansom and W. Cummins. “The Status of Women in Pictish Society.” British Archaeology (1357-4442, no. 3 1995). Tim Clarkson, The Picts a History. (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2012), 205-06.

[47] Cummins, The Age of the Picts, 125-137.

[48] Helen Oxenham. Perceptions of Femininity in Early Irish Society. (Suffolk, UK: The Boydell Press, 2017). Saga of Triduana: See Appendix B 2.

[49] Tim Clarkson, The Picts a History. (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2012) 23-45.

[50] James Charles Roy, Islands of Storm. (1st ed. Dublin: Dufour Editions, 1991).

[51] See., John O’Donovan, Eugene O’Curry, W. Neilson Hancock, Thaddeus O’Mahony, A. G. Richey, W. M. Hennessy, and R. Atkinson, trans. Ancient Laws of Ireland and Certain Other Brehon Law Tracts. (Dublin, UK: Printed for His Majesty’s Stationer’s Office Published by A. Thomas, 1865).

[52] Roy, Islands of Storm.

[53] Watcher, Roman Britain, 18-56.

[54] See., Miranda J. Aldhouse-Green. Boudica Britannia. London, UK: Routledge, 2016.

[55] Clarkson, The Picts a History, 23-45.

[56] Clarkson, The Picts a History, 23-45.

[57] Alfred P. Smyth. Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80-1000. (Edinburgh, SCT: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), 136-140.

[58]Anna Ritchie, Perceptions of the Picts: From Eumenius to John Buchan.

[59] F. T. Wainwright, The problem of the Picts. (Edinburgh: Nelson, 1955) 116.

[60] Ritchie, Perceptions of the Picts, 20-30.

[61] Ritchie, Perceptions of the Picts, 20-30.