Men’s natures are alike, it is their habits that carry them far apart.

Confucius, The Analects

Traditionally, Chinese have regarded China as the centre of the world, demonstrating diminutive awareness of foreign lands. Before the 1820s, China had little contact with Western powers but the Frist Opium War brought the West cascading down upon an unprepared China. In the late Qing period, China was undergoing a torrent of transformations during which the West challenged the fundamental principles of Chinese society. In response, to the upheavals in their society scholars like Wang Tao began the long process of coming to terms with how to deal with the West. Conversely, Westerners like the Protestant Missionary James Legge began to realise that China had a wealth of classical literature that worthy of study and to be transmitted to the West.

Over the course of the 1850s and mid-1860s, the turbulent events in China would eventually facilitate the meeting of James Leggel and Wang Tao in Hong Kong in 1863. Through this chance encounter and their emerging mental shifts, they began a process of cross-cultural exchanges that would profoundly affect the lives of both men. With assistance of Wang Tao, James Legge would become a noted Sinologist and translator of classical Chinese literature. Equally, James Legge would offer Wang Tao the opportunity to explore Europe, which would set him on the path of an ardent reformer.

In regards to the sources the author has used as the foundation of his research, there are two principle types: primary and secondary. The author only employed two primary sources: Helen Edith Legge’s half autobiography entitled James Legge, Missionary and Scholar and Wai Tsui’s translation of Wang Tao’s Jotting of my Roaming. The central secondary sources are biographical accounts of both Wang Tao and James Legge. The first is Norman Girardot’s The Victorian Translation of China: James Legge’s Oriental Pilgrimage and the second is Paul A. Cohen’s Between Tradition and Modernity: Wang Tao and Reform in Late Ch’ing China. By combining these sources one is able to discover the extent to which Wang Tao affected James Legge’s view of China and his translations. Likewise, the same is true for Wang Tao. By examining these sources one can observe how James Legge enable Tao to transform into the journalist and fervent activist for Western-style reforms within China.

As a final point, the author judges that the research explored in this paper will further our understanding of Wang Tao by demonstrating that his influence helped span the divide between China and the West. Moreover, the paper serves to call attention to the fact that Wang Tao had some influence upon James Legge’s translations of classical Chinese texts, which furthered the cross-cultural exchange between the East and West. Moreover, those exchanges broadened both men’s perspectives and enabled them to achieve a moderate amount of success in their lifetimes. James Legge went on to become an advocate for the study of Chinese texts biased solely on their cultural merits. Wang Tao would become known in his own right as one of the founders of Chinese journalism and an advocate for Western-style reforms within China. The mere fact that many Western scholars have discounted Wang’s part in the development of British Sinology reinforces the need for further scholarship on the subject. Furthermore, the author anticipates that this humble research paper might bring forth renewed academic attention to Wang Tao, whose achievements have been wholly neglected by recent Western scholars.

When examining China in the mid-nineteenth-century, one notices a civilisation in flux, a nation torn between the past and every present force of change. Confucian China segregated from the rest of the world by choice and thoroughly narcissistic had hardly any inclination for what was in store for it. Accordingly, China, in the latter half of this period, found itself at a significant juncture in its historical development. The Qing Dynasty was in rapid decline, and unable to enforce its isolationist stance, which made the country vulnerable to European powers. During this period, China was inundated with immense tribulations and threatened with unparalleled challenges. Nevertheless, the opportunity for necessary change emerged as it had never before. It was in this turbulent historical period that one observes the compelling story of two men who were manoeuvred together by these contingencies. On one side stood James Legge, a nonconformist Scottish Protestant missionary who chose to bring the word of God to the “heathen Chinese.” On the other hand, stood Wang Tao a rebuffed Chinese scholar-gentlemen of the first degree, who scorned Westerners and resented the Qing imperial system. Together they began a process of cross-cultural exchanges that we are still in the midst of today. Yet, though from different backgrounds and societies, the two men had a similar shift in how they thought about one another’s society. This modification of thought made it possible for both men to appreciate each other’s civilisation and to attempt to understand it through intimate contact with the opposite. Such shifts in one’s worldview are usually a gradual process, and that was the case with both of these men.

Nonetheless, once that mental shift had occurred, both men went on to advocate for mutual appreciation of each civilisation’s cultural achievements. James Legge would become one of the most famous British Sinologists of the nineteenth-century and assisted the Western scholars in attempting to comprehend the classical Chinese texts. Conversely, Wang Tao found traditional paths to official office closed to him and became a pioneer in journalism, who ardently advocated for Western-style reforms in China. And yet, before the 1890’s, very few Westerns or Chinese were able to make that mental leap and act upon it. Such an occurrence raises two important historical questions: First, what were the unforeseen events that transpired to place these men in the same place, where they could shape the other’s opinions? Second, why were Wang Tao and James Legge different from other scholars of the era? Answering these complex questions is the central focus of this paper. Through the exploration of these queries, one can tease out how both men were transformed by their experiences and by what each gained through their long association. From this information, it will become evident that Wang Tao had a significant impact on James Legge’s mental pivot, or what Legge’s biographer J. Girardot terms his hyphenation,[1] from a dogmatic missionary to an engaged scholar with a genuine appreciation of Chinese art, music, and literature.

Biographical Information

Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums Collections

James Legge

On the one side of this exchange stood Scottish Protestant missionary James Legge. A.F. Walls called him, “probably the most important sinologist of the nineteenth century.”[2] Born in 1815, at Huntly, in Aberdeenshire, he was the fourth son of a reasonably prosperous merchant. A talented young lad, Legge earned an M.A. at King’s College, Aberdeen. After joining up with the Congregational Church, Legge completed his four-year missionary studies at Highbury College, London in just two years.[3] In 1838, he was nominated by the London Missionary Society to join the Chinese mission station in Malacca. Upon hearing his coveted nomination, Legge eagerly applied himself to learning the Chinese language with the aid of a translated New Testament and a version of the Analects. [4] While Legge was an accomplished translator, there was something peculiar about the way converted languages into English that is worth mentioning. First, he would translate an English text into the language he was working with then translate it back into to English and compare it to the original. Legge argued that it was through this process he was able to acquire the talent for the translation of foreign languages. [5]

Once in Malacca, he became principal of the Anglo-Chinese and moved with the mission to Hong Kong in the aftermath of The First Opium War in 1843. The Treaty of the Bogue relaxed restrictions on Western missionaries and granted the British access to Canton by way of Hong Kong. It was in this new posting that Legge began to feel the desire to know his enemy by translating the Four Books and Five Classics, which would “serve as a standard for foreign students of Chinese literature, and lay open to the general reader the philosophy, religion, and morals of that singular people.”[6] Accordingly, it is this period that we first begin to see shifts in Legge’s thoughts concerning the Chinese civilisation. Legge writes that Chinese literature is a repository of a great story that merits translation for its own sake.[7] However, Legge still held insensitive and harsh opinions about classical Chinese texts. He would need further experience and interpersonal exchanges to reach a point where he would be able to make that mental shift towards a genuine appreciation of Chinese literature. Shortly after his arrival in Hong Kong, the London Missionary Society changed the college into a theological seminary, and Legge continued as its headmaster until 1856. Also, during this period Legge became the minister of the English Union Church and facilitated the growth of a Chinese congregation.

In the midst of all his professional obligations, he worked tirelessly to translate the Analects (1861), and a seven-volume translation of The Book of Documents (1865) into English. Legge’s first translation of the Analects was stuffy and mechanical, which reflects his views of the Sage. But, in 1863, Wang Tao joined Legge’s translation project as an assistant after Hong Rengan had left. From this point on Legge would undergo a transformation in his thought processes that would change his perception of the classical works that he was translating. In comparison with his argumentative tone in the first publication of the Analects, his later works demonstrated a more developed and objective scholarship. In part, this shift was due to the ten-year collaboration with Tao. Where Legge’s depth of knowledge in the classics had grown more intimate, and his appreciation of Chinese thought had matured. [8] A consequence of this was that his contemporaries often chided him for his appreciation of Confucius and his belief that the Chinese classical texts contained some fundamental truths.[9] Nonetheless, such was the familiarity of their collaboration that when Legge returned home to Scotland in 1867, he invited Tao to stay with him while they finished translating the Chunqiu. He then returned to Hong Kong as pastor at Union Church from 1870 to 1873. While there he published The Book of Songs in 1871 with the assistance of Tao. In 1875 Legge was chosen as a fellow at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, and was the first professor of Chinese studies there until his death at Oxford in 1897.[10]

Legge’s academic legacy would be overshadowed in the years after World War I by academe’s secularization and the sense that his Christian worldview vexingly contaminated his work.[11] While his translations and other works do contain such limitations, Legge’s legacy can be observed in his forthright pursuit of cross-cultural intercourse. His later examinations of the Chinese classics were conducted in a way that honoured their uniqueness and intricacy. Such explorations will always be contaminated by bias and will never achieve complete impartiality. Accordingly, Legge’s contribution rests in his desire to comprehend a distinctive civilisation and to respect it for its otherness. Is this not the greatest duty and purpose of all those who pursue scholarly endeavours?

Wang Tao

Wang Tao was born as Wang Libing in Luzhi, near Suzhou, Jiangsu province, China, in 1828. He is often remembered as one of the forerunners of contemporary journalism in China and a leader of a reform movement that sought to transform China’s out-dated institutions with innovation brought about through contact with the West. Tao’s father, Wang Ch’ang-kuei, earned a living as a tutor of young men wishing to take the imperial examination in order to obtain an official position within the Qing Imperial Government. Naturally, Tao’s father undertook his education, which was grounded in classical Confucian literature. In 1845, he passed the first level exams with distinction and was esteemed by the examination officials for his abilities.[12] The following year he went to Nanjing to take the second tire of exams, but he failed the eight-legged essay portion of the exam. Tao’s failure would make him ineligible to hold an office within the Qing government. Like many ambitious young men of the age, the failure of the imperial exams was a crushing blow, which led to ardent criticism of the examinations and the calls for its removal. Tao seemed to have developed this view of the tests early on in his life and refused to take the exam a second time, claiming that there were better ways adhere to one’s filial piety.[13]

In 1847, Tao’s father took a teaching position in Shanghai and he would often visit his father there. After these trips Tao would muse about the crudeness of the barbarian merchants (Westerners) and how their presence threatened China. He criticised the Qing government for its policy of peace and urged for the bolstering of China’s costal defences.[14] However, tragedy struck in 1849 when Tao’s father suddenly died. Overnight, he became the sole provider for his mother and younger brother, as well as his own growing family.[15] Using his father’s associates, Tao engaged Walter Medhurst for a position and Medhurst invited him to serve as the Chinese editor of the London Missionary Society’s printing operation in Shanghai.[16] Despite his misgiving about working for uncouth barbarians, Tao decided that the pay was decent enough to endure the machinations of these foreigners. However, he complained bitterly about his work at the press and concluded: “even Confucius, if resurrected, would have found it impossible to correct their compositions.”[17] Regardless of his personal misgiving, he assisted Medhurst in his translation of the New Testament into Chinese and would work at the press for the next thirteen years. It is also, during this period that Tao converted to Christianity and was baptized in 1854. While, missionaries did not require conversion of their staff, if one did convert it would enhance their position and offer job security.[18] Nonetheless, Tao seems to have been nonchalant towards his belief in Christianity,[19] which is evident by his lifelong enjoyment of drunken debauches and his constant philandering.[20]

Throughout the tumultuous 1850s, Tao remained aloof from the widespread Taiping Rebellion, but in 1860 he began to offer his opinion to Qing authorities on how to deal with the uprising. In 1862 Tao received word that his mother was dying, and he was obliged to travel to Luzhi to assist his mother. However, Luzhi was located within Taiping controlled territory. While in Luzhi, his frustration with the Qing government boiled over into a scathing essay entitled “I-t’an,” where he criticised the ineptitude of the government’s handling of the war. Yet, Tao’s proposal was not the instance that would lead to his downfall. In the aftermath of the battle of Wang-chia-ssu, a proposal written by a one Huang Wan was discovered in the Taiping’s discarded baggage. The contents of the letter explained how the Taiping forces could take Shanghai and advocated for the engagement of foreign powers to aid their cause.[21] Local Qing authorities in Shanghai conclude that Wang Tao must have written the letter. Upon returning to Shanghai, Tao was obliged to seek refuge in the British embassy because Qing officials want to execute him as a traitor. After a long political stalemated, the British ambassador, possibly at the behest of Medhurst, spirited Tao away during the night and exiled him from Shanghai.[22]

Compelled to flee to British-controlled Hong Kong, Medhurst or Muirhead had given Tao a letter of introduction to the London Missionary Society of Hong Kong’s director, James Legge.[23] Over the next ten years, Tao would assist Legge in his monumental translation of the Five Classics of Confucianism and would spend an additional two years in Scotland working on other translations. While, in Europe, he would spend the majority of his free time becoming familiar with Western institutions, technology, education, and the means of production.[24] Returning to Hong Kong in 1870, Tao was determined to make a living as a writer, so he became an independent reporter, establishing one of the first modern newspapers in China; the Tsun-wan yat-po.[25] Later, he also wrote for the prestigious Shanghai newspaper Shen Bao. Tao used the newspapers as a platform to express his opinions on reform and for criticising the ineptness of Qing government. In his editorial columns, he advocated for the introduction of Western-style factories, dockyards, rail transit, and mining operations. Most importantly, Tao argued that the West’s strength did not lay in its military might alone; rather its true power lay in the superiority of its democratic political institutions. Wang did not see Western institutions as something alien to China but felt that such ideas were underlying notions to be found within Confucian thought. Tao’s writing would go on to influenced a whole generation of Chinese leaders, including the famous scholar-reformer Kang Youwei and the renowned Chinese revolutionary Sun Yat-sen.[26] Such is the celebrated legacy of Wang Tao, a man spurned by the old guard who would usher in a new political order and offer China a new path in an increasingly interconnected world.

Historical Context

The Opium Wars

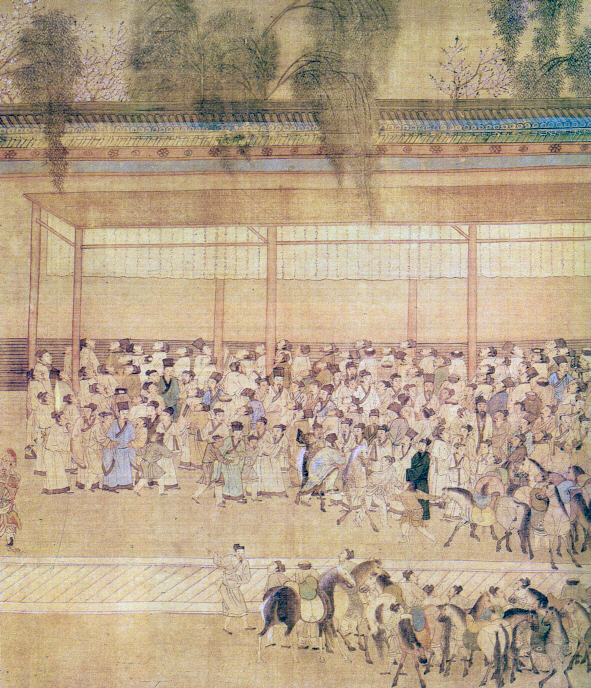

Recalling the first research question: What were the unforeseen events that transpired to place these men in the same place, where they could shape the other’s opinions? To answer this question, one must take note of the tremulous events occurring during the mid to late 1800s in China. Namely, we must explore the contingences and implications of two momentous events, The Opium Wars (1839-42, 1856-50) and The Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864). Beginning in late 1820s, British merchants began to smuggle into China large quantities of Indian opium.[27] The opium that British merchants were pushing was much more potent than natural sources, and the demand in China for this powerful new version of the drug exploded. In response to this drug epidemic and to reassert their sovereignty, the Qing government imposed a ban on opium importation in 1839. Then the Qing government seized and burnt over a million kilograms of opium stored in British merchant warehouses at Guangzhou.[28] Shortly thereafter, hostilities broke out when British naval vessels attacked and defeated a Qing blockade of the Zhujiang River north of Hong Kong. In 1840, the British sent an expeditionary force to China and proceeded up the Zhujiang River estuary to Guangzhou. After months of negotiations, the British assaulted the city and subjugated it in 1841.[29] Successive British campaigns over the next few years were equally fruitful against the mediocre Qing armies. The British held the offensive and captured the Qing capital, Nanjing, in August of 1842, which temporarily ended the conflict.[30]

With the cessation of open hostilities, the opposing parties contracted The Treaty of Nanjing, and the Qing government was forced to pay Britain a substantial reimbursement for her losses in commerce. In addition, China was required to cede Hong Kong Island and raise the number of treaty ports, where British commercial interests could ply their trade, from one to five.[31] Further privileging of British interests in China occurred with the ratification of The Treaty of the Bogue in 1843, which granted British citizens the right to be tried in English courts and bestowed on Britain the coveted most favoured nation status.[32] Indeed, it was these treaties that made James Legge’s missionary work possible. The treaty conditions reduced restrictions and made the role of professional missionaries possible, as well as problematic. Precisely because Chinese officials generally regarded missionaries as part of the militarily imposed precursor of Western interference, an uneasy tension continued to govern the relationships between foreign missionaries and Imperial authorities. These tensions were escalated further after the Second Opium War (1856-1860). Explosive xenophobic reactions from Confucian civil officials often met cross-cultural endeavours made by missionaries.

The consequence of these events on the Chinese psyche was two-fold. First, it created much consternation in the mind’s Chinese scholars, who could not grasp that the West was a fundamental challenge to the Chinese civilisation. This failure to understand their present situation stems from the idea that China was the centre of the world and that China’s cultural norms were universal. Broadly this worldview meant, that for a person to be civilised one must be Chinese or emulate the sophistication of their norms. This line of reasoning also implies that everyone else was the disdained “other” or barbarian. [33] It is important to note that this narrow worldview was not exclusive to the Chinese, rather can be found in classical and modern European civilisation. A classical European example would be the Athenians during the Greek classical period, where the English word barbarian (βάρβαρος) originated.[34] Such notions seem to be an inherent flaw in the human condition.

Second, historically, Chinese society had always absorbed it’s conquer and only one other civilisation, India, was able to influence China deeply through the introduction of Buddhism. Until the nineteenth-century, China had not encountered a civilisation that challenged its own refinement and had the resources to enforce its will within the country. These two points taken together meant that China was, for the most part, ignorant of the West for most the late 1800s. This state of ignorance is not to say that China did not understand that it needed to adopt Western technologies for security purposes. Rather, it meant that Chinese scholars rarely found it prudent to study barbarian societies because, by definition, they were not worth considering. Such a worldview was Wang Tao’s stance during the 1850s, and one finds an overtly negative view of Western civilisation within the majority of his writings. However, the events of this period would shift the focus of Chinese concern from the internal to the external menace. In the wake of this latent realisation, Tao would pen a long letter to a friend wherein he outlined his ideas concerning Western-Chinese relations. He criticised prevailing views of the treaty port Chinese and argued that whatever the advantages in trade with Western powers, it would expose China to greater harm in the future. The Western threat to China was not exclusively a military one. Tao railed against Western ideas as fomenting dissent and poisoning the minds of the people. He writes that Western notions are “to be feared that as resulting in great harm to Confucian values.”[35] While he did not reject Western technology outright, like some of his peers, instead he reasoned that even Confucius went to the four corners of the empire in his pursuit of knowledge. Paramount in his argument was the immediate adoption of Western arms and steamship so that China could defend herself against the barbarian. Lastly, Tao reasoned that history was cyclical. In Tao’s recurrent historical paradigm, China was on the downward track of the cycle, but when China was flourishing the nations of the world submitted. Consequently, the reason why Western powers had defeated China was that she was, for the moment, in a state of decline, but the Chinese knew that such an occurrence was nothing new in her long history. “Indeed! From ancient times down there has never been a country that has perpetuated its power.”[36] Thus, the same law of history must also be true for European powers. [37] Wang Tao’s early appraisal of Chinese-Western relations contained notions, such as a cyclical view of history and a recognition of the West’s superiority in the field of technology, which would remain central to his views later in life. However, his personal correspondences were still filled with derogatory descriptions of Western’s as the uncouth barbarian. Tao, like Legge, would need time and the bitter teaching tool of experience to bring about the shift in his worldview.

A comparable set of dogmatic beliefs held sway on the Western side. The First Opium War (1839-42) was the first large-scale military action between the Qing Dynasty and a Western imperial power. After the Qing government had destroyed the British merchant’s opium at Guangzhou, the Metropolis responded by sending in the Army, which was supported by the unchallenged Royal Navy. The result of this war not only leads to China’s loss of Hong Kong Island but also exposed the military feebleness of the Qing government. Up to this point, Western powers had maintained a cautious and conciliatory foreign policy toward the Qing Empire. But after the war, Britain began to assert its authority over China and imposed upon it a series of disadvantageous economic treaties. As a result, the legacy of the First Opium War was to further Western imperial aggression within Qing affairs and the denigration of Chinese civilisation in the minds of Westerners.[38] Consequently, in any brief survey of English history, one will find that the English are ethnocentric and violently debased other societies that they viewed as barbaric.

Like Tao, James Legge was not immune to such haughty beliefs, which can be humorously demonstrated by the fact that shortly after leaving England for Hong Kong he began to swagger about the deck of the ship in a flamboyant white planter’s suit.[39] Akin to other merchants and missionaries of this period, Legge was seeking an enterprising fame in foreign lands, which was the typical extension of English Victorian ideas of social fulfilment. Indeed, such was Legge’s initial hauteur that, while in Batavia, he and Walter Medhurst had such contempt for the Chinese that they instigated a debate in a shrine to Tianshang Shengmu. Medhurst harshly denigrated the attendees for the foolishness of their henotheistic beliefs and urged to toward Christianity, Legge later wrote that he concurred with Medhurst’s conduct.[40] Clearly, Legge had a long road ahead of him on his journey toward shifting to cross-cultural intercourse and an appreciation of Chinese society. Despite this initial defamation, he would spend the greater part of this life combating the deprecating views that he once held. These changes in his perceptions would become more manifest the more he studied Chinese civilisation and associated with Chinese scholars. In time, Legge would become fascinated with China, not because of its need for conversion. Rather, he would develop an academic attraction of wanting to know about China for its own sake. Because, China was a repository of its own great tradition that needed to be translated, studied, and esteemed on its own terms.

With that said, another interesting factor in the aftermath of The Opium Wars is Legge’s connection to the opium trade through his association with the Jardine Company, one of the leading opium merchants in China. In 1856, Legge tapped into the wealth of the opium trade by soliciting Joseph Jardine to put up the funds to publish four of his translated Chinese classics. Jardine would become one of Legge’s most steadfast financial backers and assisted in sponsoring the majority of Legge’s publications of Chinese Classics. Such secular patronage shows how important charitable interests played a significant role in supporting Legge’s scholarly endeavours. The duality here is that Legge’s academic distinction and his life’s work were, in part, funded by opium.[41] Such a relationship is curious, given the fact that Legge was a founding member of the Anglo-Oriental Society for the Suppression of the Opium Trade and he called the opium trade “a curse to China and a disgrace to Britain.”[42] While one must be cautious about drawing blatantly negative conclusions from this, one can clearly observe the complex and dynamic nature of this period. Furthermore, one can observe that both Legge and Tao had considerable obstacles to overcome before their mental shifts would occur. But, tremulous events in China would soon come about that would initiate this process of cross-cultural exchange and mutual respect within these two men.

The Taiping Rebellion

With the onset of the Taiping Rebellion begins a series of events that would bring Tao and Legge together in Hong Kong, where they would spend the next ten years together in close association. The Taiping Rebellion was a sweeping political and spiritual cataclysm that was probably one of the most important events in China during the nineteenth-century. In 1843 a young man named Hong Xiuquan, in the southern providence of Guangdong in China, failed his civil service examination for the fourth time; a frustration that Tao knew all too well. It was this failure, which moved Hong to take up arms against the ruling Qing dynasty and establish the Taiping or “Heavenly Kingdom.” Inspired by Christian teachings and disillusion by the miserable plight of the people, Hong cast himself as a brother of Jesus Christ and vowed to purify the nation. The subsequent rebellion was to last for almost fourteen years (1850–64) and struck a mortal blow right at the heart of the Qing Imperial forces. It was also particularly brutal, during the conflict an estimated 20 million lives were lost during the struggle, and it permanently debilitated the Qing dynasty.[43]

The Qing dynasty had been one of China’s greatest and most flourishing Imperial families. But, by the middle of the nineteenth-century, a whole variety of different factors were causing it to fall apart. Chief among these issues was the British importation of opium into the country, which were breaking down a lot of the social norms of Chinese society. Internally, the country simply was not bringing in enough taxes to maintain a well-equipped standing army. Essentially, we have a once vast empire that is slowly collapsing from within and being pushed from outside. In this situation was the right possibility of social turmoil. Compounding this problem was an increase in population, which the Qing government failed to keep pace with in regard to civil administration. The result was an unstable social situation with a lot of impoverished and disenfranchised young men, who had no prospects for the future.[44]

It was in this deteriorating situation that Hong, like thousands of other young men, had failed to pass his civil service examination. At some point, when Hong was in Canton for one of his examinations, he was given a Protestant religious pamphlet written by a Chinese convert. Later, he fell ill with a fever and began to have delirious dreams. In those dreams, God told Hong that he was his son and Jesus Christ’s younger brother. It was from these dreams that Hong began to believe that he was a messiah sent by God. However, Hong’s views on Christianity seem to be a bit skewed and American Baptist pastor, Issachar Roberts, refused to baptize him because Roberts held some doubts about the nature of Hong’s beliefs.[45] Later when Hong created the Taiping movement, he promised the masses of dispossessed an extreme form of egalitarianism loosely wrapped in Christian rhetoric and violent militancy. This message of a shared stake in the government and anti-Manchu rhetoric attracted a multitude of peasants. In a short time, Hong’s followers went from a few thousand to one million.

The armed conflict commenced in 1851, when the Qing forces launched an attack against Hong’s followers, the God Worshipping Society, in the region of Guangxi. Sweeping north from south-western China, the Taiping quickly dispersed the Qing government forces and captured the city of Nanjing in 1853. Nanjing is a key strategic city because it was where the main terminal for tribute grain begins to travel up the Grand Canal to Beijing. Hence, to hold Nanjing is to hold the Qing Empire by the throat. Essentially the capture of this vital city is the point where the Taiping’s switch from being insurgents or revolutionary’s to actually being an alternative state within Chinese territory. As a consequence, thousands of spurred and able young men flocked to the Taiping standard. These ambitious and discontented men would fill the organisation of the Taiping movement, which was intensely autocratic. At the top of the leadership structure are a number of kings that control policy based on dreams or trances where God would communicate directly to them. Legge’s assistant Hong Rengan would become one the Taiping’s Prince Gan, essentially a role resembling a Prime Minister. However, Hong Xiuquan increasingly began to retreat into his inner place and to behave erratically. Were the “Heavenly King” surrounded himself with a harem and shut himself away within the place, leaving Hong Rengan to be the acceptable face of the Taiping government.[46]

Conversely, Qing forces proved to be largely ineffectual in halting Taiping expansions throughout central China and, instead, focused the bulk of their troops in the bogged down siege of Nanjing. In the end, the Qing government would need the assistance of foreign nations to defeat the Taiping threat. In the meantime, the Taiping government was thrown into chaos by political infighting and usurpation. The Dongwang (Eastern King), Yang Xiuqing, began to appropriate and infringe upon the powers of Hong Xiuquan. Hong then ordered Yang and thousands of his attendants put to death. Shortly thereafter, Taiping generals Wei Changhui and Shi Dakai began to desire more power. Wei was put to death, and Shi escaped with life, but many of Hong’s supporters followed Shi into exile.[47]

In the 1860s, the Taiping’s made a strategic miscalculation by deciding to attempt to take Shanghai, which would lead to their eventual defeat. For the Taiping, this move made sense because Shanghai was the centre of Western trade, wealth, and military technology within China. After a string of humiliating defeats, the Qing government was forced to ask for assistance from Western powers because they could not defend, Shanghai. In response, American Frederick Townsend Ward began to recruit Westerners for his planned filibustering expedition against the Taiping’s. The Western “Ever-Victorious Army” aided in the defeat of the Taiping forces around Shanghai and was successful in other engagements. More important than Western soldiers, was the military technology that the British government began to supply the Qing army. Qing troops began to use this new weaponry to retake fortified cities held by the Taiping. Another significant factor in the defeat of the Taiping was the loss of support from the aristocracy. Initially, these men rallied to support the rebellion, but the “Heavenly King” had alienated them through his radical anti-Confucianism polices. Observing the Taiping defeats, they united under the leadership of Zeng Guofan, who organised the Xiang Army.[48] By 1862 the Xiang Army had pushed the Taiping to back to Nanjing, and the city fell in July 1864. Hong Xiuquan died of food poisoning in June and installed his was son as king. Hong Rengan attempted to escape with the young king but was captured by Qing forces and beheaded. Upon hearing of Hong Rengan’s fate, James Legge lamented his death, “My old friend Hong Rengan, was prepared to counsel them [Taiping] wisely…but was not equal to the difficulties of his position.”[49] Those tumultuous events essentially denote the end of the Taiping rebellion, though intermittent resistance continued until 1868.[50]

James Legge’s Taiping Connection

The abovementioned point, about the Taiping’s as a rival to the Qing state, is how one should view the movement. The reason that we should think about the Taiping’s in that way is due to the fact that foreigners spend a lot of time attempting to decide which of these regimes they should support. One of the reasons for the British seriously contemplating supporting the Taiping’s is due to the singular efforts of Hong Rengan, who had become the prime minister of the Taiping government. Rengan is Hong Xiuquan’s cousin and, while he was on the run from Qing authorities in 1854, James Legge gave him shelter at the London Mission Society seminary in Hong Kong.[51] Rengan continued in Legge’s employ as a translation assistant until 1858 when Hong Xiuquan asked him to join his government. With the enthusiastic encouragement of other Western missionaries, he then disguised himself as a peddler and made his way to Nanjing. Before Legge left for England, he told Rengan to stay out of the rebellion.[52] Once in power, he puts forward ideas that are supposed to solidify the movement. In other words, he sets up a new type of government based on this idea of Christian doctrine that was enhanced by his association with Legge and other Western missionaries.[53] Indeed, Rengan corresponded with Legge seeking clarification on religious issues and proposed policies.[54] Rengan’s vision of government also included Western institutions; for example, he formulated plans for a banking system, post office, railways, and newspapers. All of these proposals were written down and brought to Hong Xiuquan as a set of policy strategies. One of Rengan’s reasoning for these Western policies was that if the Taiping government supported them, then they would be able to attract international recognition, which would declare that they were a stable and reliable state.[55]

Shortly after Rengan’s departure, Legge would publicly express his regret for the lost opportunity for international recognition of the Taiping government.[56] Legge began to write a series of editorials protesting the British government’s intervention on the side of the Qing dynasty. Legge states that he objected to this military effect for two main reasons. Firstly, he laments that immense cruelty of the civil war upon the average civilian. Legge recounts the plight of the people who have suffered greatly at the hands of both sides. However, the Imperial Government forces behave like “the progress of locusts” leaving only devastation in their wake.[57] Furthermore, Legge states that if the British entered the war on the Qing side, one would just have to remember that the Imperial forces under Yeh beheaded 70,000 civilians over the course of twelve months in Canton during the onset of the First Opium War. Conversely, the Taiping were less likely to threaten civilians outside their controlled areas.[58] Nonetheless, Legge is glossing over the fact that the Hong Xiuquan’s divine visions would quickly spiral out of control and lead to absurd prohibitions on all sorts of acts, all of which were punishable by death.[59]

Secondly, Legge argues that the Qing is incompetent and everywhere its officials are corrupt. Moreover, one finds in areas not controlled by the Taiping, the people are openly defiant and oppose the Qing officials. Furthermore, without a treaty, the Taiping are already in open commerce with the British and that most of the British trade flows from Taiping controlled areas. Thus, attacking the Taiping would go against Britain’s commercial interest. From these points, Legge concludes that any treaty with the Qing government would be unenforceable. Moreover, Qing soldiers are cowards and wasting British lives to support such supporting such a government is utter folly. At its core, Legge’s argument is that the “Manchus are not worthy” and that any treaty that enhanced the British standing in China would be a “vain dream” that would also be a “thankless and uncertain undertaking.”[60] In many ways Legge’s assertions were correct, but the Taiping were far from a stable government and its leader, Hong Xiuquan, would become increasingly erratic as the rebellion fell apart from within. Nonetheless, from these objections, it may be possible to infer that Legge offered Wang Tao his position at the London Missionary School out of genuine remorse or regret concerning the fate of his noble friend Hong Rengan. Indeed, such was Legge’s admiration for Regan that he mentions his name, along with Ho Tsun-sheen and Wang Tao, as “one of the most intelligent and impressive Chinese” that he had ever had the pleasure of meeting.[61]

Wang Tao Pursues A Governmental Appointment

Recalling that the Taiping were a rival to the Qing state, Wang Tao was also enticed to seek out an official appointment within the Taiping after years of rejection from the Qing government. In spite of this, like many who flocked to the Taiping banner, Tao’s did not find the rewards he was seeking. His actions would set into motion his exile to Hong Kong and his to subsequent relationship with James Legge. In the beginning, however, Tao attempted to find favour with the Qing government by writing to a series of proposals explaining his opinion about how the government should conduct the war effort. In the first proposal, he highlights the importance of Shanghai and how the government should secure it from the Taiping rebels. In the second set of suggestions, he outlines a decent battle plan that consists of peasants acting as partisans to disrupt the Taiping movements and deny them the countryside. Sadly, his well-thought-out proposals fell on deaf ears, and local Qing officials spurned his efforts.[62] Tao would see these rebuffs as further evidence of Qing mismanagement and ineptitude, which did not allow them to recognise his potential.

While the local Qing officials in Shanghai blundered around in a state of near buffoonery, Tao’s mother in Luzhi fell ill and was thought to be near death in January of 1862. Once he received the word concerning his mother’s illness, he asked William Muirhead (Walter Medhurst left the Shanghai mission in 1856 due to poor health) for a leave of absence in order to attend to his ailing mother. Muirhead reluctantly granted his request, because Luzhi was deep within Taiping held territory, and he cautioned him to not to tarry too long or to openly associate with the local Taiping authorities. His stay in Luzhi lasted three and a half months. The delay in his return to Shanghai was allegedly due to poor weather and fierce fighting.[63] However, while in Luzhi, his frustration with the Qing government boiled over into a scathing essay entitled “I-t’an” (Presumptuous Talk). He wrote the scathing assessment with forty-four parts that he modelled on political critiques of the T’ang and Sung periods.[64] Wang Tao’s biographer, historian Paul Cohen, contends that his writings in the “I-t’an” echo Huang Tsung-his (1610-1695) in his classic reproach of Imperial despotism entitled Ming-i tai-fang lu (A Plan for the Prince). Tsung-hsi’s work argues for greater real-world knowledge for local administrators and a greater emphasis on the government official with expertise in a particular area.[65] Similarly, in the “I-t’an” he vehemently criticised the ineptitude of the government’s handling of the war. Tao contends that the solution to the government’s failure to contain the rebellion can be found in the core Confusion concept of remonstrance. The government needed competent officials and an efficient state administrative system; not one’s prone to servile flattery. Unsurprisingly, the Taiping officials rejected his well thought-out and argued advice.[66] Nevertheless, it was this proposal that contained the seeds of Tao’s downfall and exile to Hong Kong.

Tao’s critique also included a detailed account of the defence capabilities of Qing and Foreign military assets, as well as their strategic placement around Shanghai. Moreover, the proposal counselled that the Taiping forces should reframe from attacking foreign military personnel because the British were a powerful enemy and would spare no effort to avenging any deaths that may occur.[67] Tao’s essay came to light in the aftermath of the battle of Wang-chia-ssu, when a proposal written by a one Huang Wan was discovered among the discarded baggage of the retreating Taiping commander. Hastily, written at the end of the essay was a note that said, that the strength of the Qing forces should not deter the Taiping from attacking Shanghai once a negotiated settlement was reached with the Western powers.[68] Once discovered, the Local Qing authorities in Shanghai quickly concluded that Wang Tao must have written the letter.

After such a prolonged absence Muirhead asked Tao to return to Shanghai, and he promptly did so. Fearing that he would make not be able to safely through the lines, Muirhead asked the Qing authorities to grant Tao safe passage, to which they agreed. However, upon returning to Shanghai, Tao was forced to take refuge in the British consulate, because Qing officials want to arrest him as a traitor. Somehow, Tao made it past the Qing troops guarding the gates to the city and made it to Muirhead. Hearing that the Qing authorities were searching for him, Muirhead then shuttled him off to British consulate. Working at the consulate was Walter Medhurst Jr., who agreed to offer him protection, because of his faithful service to his father at the London Mission Society Press.[69] The British ambassador, Frederick Bruce, attempted to get a guarantee from Qing authorities to allow Tao to go free but demanded that they turn him over. Thankfully for Tao, Bruce refused to hand him over, even though the British knew about his proposal to the Taiping concerning the disposition of their forces in Shanghai. In the end, the British would spirit him away aboard a steamship bound for Hong Kong in October; he sheltered at the consulate for 135 days.[70]

Despite Wang Tao’s lifelong insistence that he never wrote the “I-t’an,” both Chinese[71] and Western scholars have attributed the essay to him.[72] The actual letter was rediscovered in the Palace Museum in 1933. This discovery allowed Chinese historians Lo Erh-kang and Hsieh Hing-yao to thoroughly analyse the document. Their examination revealed four pieces evidence that demonstrates Wang Tao’s guilt more conclusively. Firstly, there is there is the matter of Tao’s pen name, Huang Wan. In Taiping controlled regions, the Chinese character Wang (王) was reserved only for the Taiping Kings. So, ordinary people used the character Huang (黄) instead. The Wan portion rhymed with his given name, which was Han. The Tao given name was assumed only after his arrival in Hong Kong. Furthermore, the character for Han is also the first character for his courtesy name Lan-ching.[73] Secondly, Wan identifies himself as a Confucian scholar from Suzhou area, whose family had been sent back to their native village. These biographical entries are an almost exact match to Tao’s circumstance during this period. Third, the vernacular and style of the proposal are similar to Tao’s writing. Lastly, the argument for maintaining peaceful relations with Western powers was a theme of Tao’s that came about in his writings during the late 1850s. Taking these four pieces of evidence into account, the case against Tao is fairly concrete. However, Tao maintained that corrupt Qing officials in Shanghai framed him, though the evidence for this cannot be confirmed.[74]

Given the evidence, the question now becomes why did he write the proposal? Ultimately, the reason why he would attempt such a risky endeavour remains to be uncovered, though treason carried with it the penalty of death. One explanation may be, as Sir Frederick Bruce contended, that Tao was merely trying to secure protection for the remaining members of his family who lived under Taiping rule.[75] The other explanation that is put forth by Lo Erh-kang, contends that Tao was a mere lapdog of the foreigners and they sent him off to facilitate negations with the Taiping or to delay the planned assault on Shanghai.[76] However, this theory is problematic because Erh-knag’s premise is contaminated by his Communist worldview, which led him to conclude that the Western interests could not have been the same as the Taiping’s.[77] Conversely, historian Paul Cohen contends that based on multiple sources, Tao had some connection to the Taiping movement and that association was his best chance at gaining an official appointment within the Taiping government. Moreover, Cohen asserts that his relationship with Western missionaries might have influenced his decision to attempt such an endeavour because Western missionaries were still expressing moderated optimism toward the Taiping movement.[78] Furthermore, Tao’s associates from the London Mission Society, Joseph Edkins and Griffith John, met with Hong Rengan in Suzhou during summer of 1860, where it seems that a man named Lan-ching was their “talented native secretary.”[79] Lan-ching is the courtesy name of Wang Tao. From the LMS records one observes that Tao would meet with Taiping officials at least two more times before 1862. Given this admission, Tao seems to have come to the conclusion that he may have been able to get an appointment to governmental office from the Taiping. Wang Tao most coveted such a position and that provided him with ample motivation to switch sides.[80] Throughout the early 1860, Tao’s frustration at the incompetence of Qing government boiled over and he went headlong in the direction of open rebellion. However, Tao would never again flirt with armed rebellion, but his scholarly revolt against the predominant social order in China would gain in momentum in the years after 1863. After his time with Legge, Tao would become one of China’s most outspoken promoters for Western-style reforms to be incorporated into Chinese government and society.[81]

Regardless of his motivations, the reasons for the British assistance to Tao remain to be revealed, however his “I-t’an” essay stands as a significant shift forward in his thinking concerning the problem of the West. The majority of his writing up until this point has been centred on issues relating to China and not one the ingress of Western influence. Even with almost a decade of employment with Westerns and his half-hearted conversion to Christianity, his thoughts seem to hardly broach the Western problem. His writings are filled with Chinese solutions to that what has become a radically different situation. While, the “I-t’an” essay still is in this thread, Tao now began to see that the Chinese must deal with the Westerns and the implications of their presence within China. Tao had a circular view of history that allowed him to use the China’s past as a force for change in the present, as opposed to other Chinese scholars who viewed history as inactive.[82]

From this brief overview of the historical record, one does appreciate the contingent events that occurred during the Opium and Taiping conflicts, which had a profound impact on the decisions that both men made would make. Moreover, it was the structure of the Qing government and its sponsorship of Confucianism that facilitated the events of this period. More importantly, these destructive and violent conflicts served to shape the thoughts of these men by forcing them to consider implications of the inevitable disruption that occurs when two opposing cultures begin sustained contact. Through his experiences of Opium Wars and Taiping Rebellion, Tao’s thoughts began the gradual progress of shifting from a Chinese-centric worldview towards one that incorporated Western ideas. The beginning of this pivot is found within his “I-t’an” proposal, where he argues that the Taiping should engage with foreigners and employ their technology against the Qing. Similarly, Legge began to develop a genuine appreciation for Chinese art, music, and literature through his contact with the intelligent Chinese scholars, like Hong Rengan. Moreover, Legge was sincerely remorseful for the immense sufferings of the Chinese peasantry during this conflict and argued for British neutrality. Gone are the haughty European colonial notions of the Chinese and in its place Legge beings to comprehend China’s history as a great story that should be told. However, the complete shift for both men lay in the not too distant future, when a refugee from Shanghai appears at the London Mission Society in Hong Kong with a letter of introduction from Muirhead. This chance encounter would initiate a decade-long process that ended in the transformation of both men’s worldviews and initiates a cross-cultural exchange that would fundamentally alter the course of their lives.

Evidence of Cross-cultural Intercourse

The second question that this paper attempts to answer is difficult given the limitations in the historical record. However, significant evidence for the shift in both men’s thought can be observed in the separate biographical accounts as written by historians’ Paul Cohen and Norman Girardot. By combining these two secondary sources, one can touch upon the evidence of the effect each had on the other. Cohen’s work on Tao is the most insightful because it explains the depth to which Tao was involved in Legge’s translation work. While Girardot’s monumental work on the life of James Legge does reveal clues to Tao’s assistance, he only mentions Tao in few passing references. However, he does note Tao’s assistance in the translations by stating that he “did all the hard textual work.”[83] Nevertheless, it was Girardot’s fleeting references to Tao that served to facilitate the questions proposed by this paper.

Regardless, both Legge and Wang only hint at their intellectual intercourse in their memoirs with passing references to their relationship. From those documents, one can construct a rather accurate portrait of both men and their friendship. In addition, the character traits that enabled both men to make that mental shift towards a mutual understanding originate from the similarity of their backgrounds. Both men were from the middle class and afforded the opportunity to attend school. While the education that both men received was worlds apart, both excelled in their studies. Hence, both men became some of the most capable men of their time. Furthermore, Legge and Tao chafed under the rigid systems in which they found themselves. Wang had failed the second level of Imperial examinations because of the eight-legged essay, which barred him from an appointment within the Qing government. Legge experienced a comparable situation with his dislike of The Missionar Kirk Of Huntly[84] and, later, in his on-going disputes with the London Missionary Society over his translation of classical Chinese texts.[85] Furthermore, both men held overtly derogatory views of the others civilisation. For instance, when London Missionary Society representative Walter Medhurst first employed Wang in Shanghai, he mockingly observed that even if Confucius returned from the dead, he would have a rough time teaching these foreigners the proper interpretation of the texts, let only who to write Chinese.[86] Wang’s observation of Westerns was common among those of the scholar-gentry class in China. In the same thread, after his first translation of The Analects, Legge stated that he could find little merit in the writings of Confucius and that the philosophies contained within were holding China back from modernity.[87] Legge’s early comments on Confucius are representative of many Western scholars’ views of Chinese civilisation. Nevertheless, from these humble beginnings, both men went to great length to acquaint themselves with other’s society. Lastly, their direct exposure to each other enabled them to detach themselves from their own values to discover the need for change, and to re-evaluate the means by which they could make that change a reality.

Upon arriving in Hong Kong, Tao was embittered and in a sombre state. Tao had grown to appreciate his life in Shanghai, and his exile to the backwaters of Hong Kong was a severe blow. En-route to Hong Kong he assumed the given name of Tao and adopted the courtesy name of Zi Qian. The central factor that assisted Tao’s reversal of fortunes was his association with James Legge. Before leaving Shanghai, it was arranged for Tao to work with Legge on his enormous task of translating the entire books of Confucius into English. In a reversal of roles, Tao was now at the forefront of transmitting China’s tao to the West. Previously Tao had been working on translating the Bible and other Western religious works into Chinese, but he was now a mediator between civilisations. Certainly, Tao was also astonished by his role reversal that he remarked, “Who would have expected the Way of Confucius to be transmitted from the East to West! In the future, the statements in the Zhōng yōng [about world unification] are to be fulfilled.”[88] A few months after Tao’s arrival, Legge remarked, “He soon established himself in the confidence and esteem of the members of the mission, and the Chinese Christians connected with it.” [89] Legge would also note that Tao was an accomplished Chinese scholar and that he had an agreeable temperament, which endeared Tao to him. Echoing Legge, Tao eventually began to see Legge not as a stern British missionary, but rather as a Westerner attempting to broaden his mind and the two became friends within a short time.[90]

By the time Tao had arrived in Hong Kong, Legge had already published the first two volumes of the Sìshū (Four Books). Now, Legge was in the process of translating the Shangshu (Book of Documents), and Tao enthusiastically took to the work of rendering this classic text into English. To aid him in this effort Tao, asked his friend Yang Xingfu to ship his substantial library down from Shanghai. Tao’s contribution to the Shangshu was considerable, and Legge duly acknowledged his efforts within the preface of the third volume of the work.

Legge appreciatively wrote,

“This scholar [Tao] far excelling in classical lore than any of his countrymen whom the Author had previously known, came to Hong Kong in the end of 1863 [sic], and placed at our disposal all the treasures of a large and well-selected library. At the same time, entering with spirit into his labours, now explaining, now arguing, as the case might be, he has not only helped but enlivened many a day of toil.”[91]

From this statement it is evident that Tao had a profound influence on Legge’s work and set the foundation for their future endeavours.

Over the course of their decade-long friendship, Tao became the conduit for the majority of traditional Chinese knowledge that Legge was exposed to. Accordingly, Tao’s work on the Sìshū was just the beginning of his efforts. Tao would go on to perform the principal work in every classical text Legge would publish through to 1885. Consequently, a careful examination of Legge’s works reveals that Tao’s influence proliferates his translations. Within the footnotes of the Shijing (Book of Songs, 1871), Chūnqiū (Spring and Autumn Annals, 1872), (Commentary of Zuo, 1872), and the Liji (Book of Rites, 1885) Legge makes numerous references to Tao’s stylistic explanations of the text’s meaning.[92] In addition to assisting Legge in translating these texts into English, Legge asked Tao to compile a meticulous set of Chinese commentaries for each of the classics that he worked on.[93] Through Tao’s guidance, these commentaries exposed Legge to Chinese scholarly opinions on the texts that were often overlooked by other foreign academics. Legge, far from seeking all the recognition, properly credited Tao for his exhaustive efforts to make these books available to Westerners. Legge’s comments within the Shijing are representative,

“There is no available source of information on the text and its meaning which the writer has not laid under contribution. The Works which he has laid under contribution, – few of them professed commentaries on the She, – amount to 124. Whaever completeness belongs to my own Work is in a great measure owing to this…I hope the author will yet be encouraged to publish it for the benefit of his countrymen.”[94]

Such praise was merited, Tao bluntly states in his letter accompanying one of his commentaries that it took him ten months to compile the work.[95] Henceforth, by 1871 Legge candidly admitted that “None but a first-rate native scholar would be of any value to me, and here I could not get anyone comparable to him.”[96]

In the intensely collaborative effort of translating complex philosophical books into another language, Tao and Legge worked in an intimate environment. Tao had become Legge’s wellspring from which he could tap into the currents of Chinese culture and further develop his appreciation of their great story. Moreover, a point that Girardot makes about Legge’s translations of the classical Chinese text suggest the extent of Tao’s influence. Girardot contends that Legge’s criticism of the complication of the traditional commentaries from the Han and Song schools is an outgrowth of him adopting the more recent critical views of Ming-Qing scholars.[97] Tao falls into this Ming-Qing scholarly tradition. Nonetheless, Legge was still his own man and maintained his intellectual individuality. Indeed, when Ernst Johann Eitel questioned Tao about Legge’s independence of any Chinese school within his commentaries on the Shijing, Tao replied that Legge “supplements the views of the one with the other or leaves the question at issue.”[98] Nevertheless, Legge’s knowledge of the classics and his confidence that he could decipher them was a result of Wang Tao’s vast summaries of Chinese scholarly commentary, as well as their close association.[99]

From this brief overview of Tao’s influence, it is fairly evident how he affected the perceptions of James Legge. The question now becomes: How did Legge shape Tao’s view of the West? In answering this question, an important point to note is that by 1865 Tao had been working alongside Western missionaries for 16 years. The key ingredient in Tao’s mental pivot was his exposure to the West, gained through personal contacts and by traveling to Europe. The missionaries Tao was exposed to were not common run preachers. Rather, these men were the scholar-elite of the Protestant mission in China. Both Legge and Edkins were men, had openly demonstrated a genuine appreciation of Chinese civilisation and that it was worthy of academic study. (Muirhead would be the exception to this due to his negative view of Asian cultures.) Consequently, Tao could no longer think of these Westerns, who had become his friends, as barbarians because they had reached across that cultural divide. Moreover, they had gone to great lengths to acquaint themselves with the Chinese civilisation and its classical literature. While these early contacts were persuasive, it was not until Tao met Legge that we see his complete mental pivot in his writings from a Chinese-centric worldview to one that envisions China incorporating Western reforms in order to compete with the West. Writing in 1865, Tao expresses the next evolution in his thinking in a letter to Li Hongzhang, the governor of Jiangsu. Tao urges the governor to embrace Western ideas and technology because it will strengthen China in the long run.[100] Tao’s proposals to Li Hongzhang stand in stark contrast to his earlier views where he was opposed to many Western ideas and the use of technology outside those with military applications.

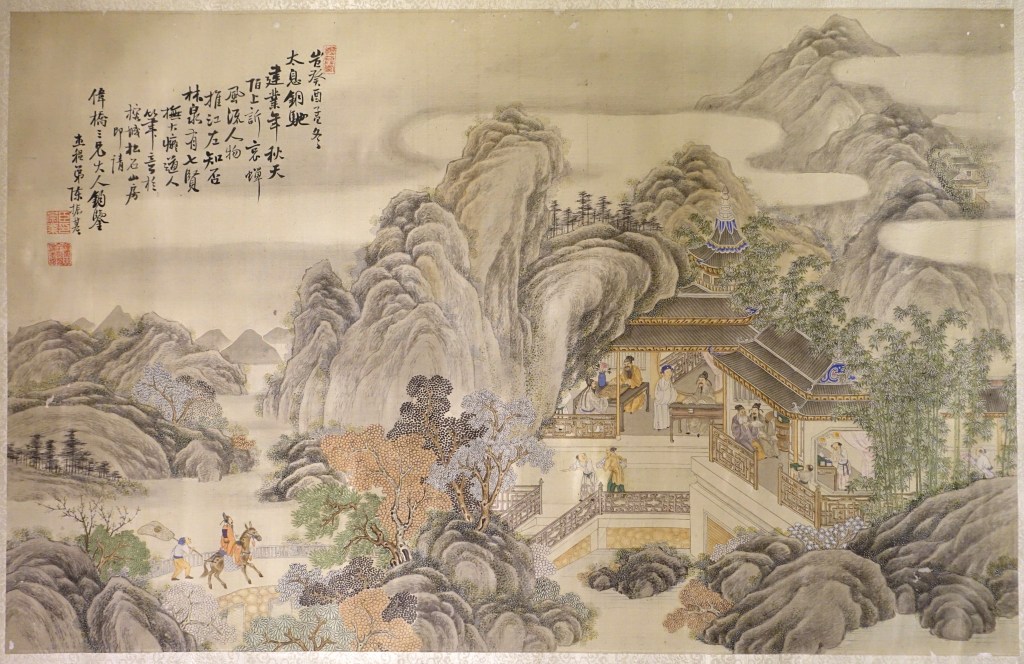

The transformation of Tao’s viewpoint would be carried one step further by his sojourn to the West in 1867. That year James Legge went back to Scotland to recover his health, but he extended an invitation for Tao to join him.[101] Historian Paul Cohen notes that Tao was most likely one of the first Confucian scholars to spend any significant time in Europe.[102] Tao wrote down many of his experiences during this journey in a book entitled Jotting of My Roaming. Fortunately, Wai Tsui, a Professor of Literature at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, has translated Tao’s travel writing into English. Wai Tsui’s work serves as a power illustration of the friendship between the existed between Tao and Legge. Over the next two years, Tao lived and worked alongside Legge in his modest two-storey home in Dollar. Indeed, the two seem to be attached at the hip and together made numerous short trips around Britain. With Legge leading the way, Tao had the opportunity to experience, in person, what the West had to offer the struggling Chinese nation.

Wang Tao boarded a steamer on the 15th of December 1867; the ship would sail through the South-east Asia making stops at Singapore and Sri Lanka. Tao, the ever keen traveller, kept a detailed account of his trip and used it as the basis for Jotting of My Roaming. The account is infused with a variety of happenings and occurrences that fascinated his eager mind. From Sri Lanka, the ship made it way up the Gulf of Aden to the Red Sea where they transferred from Suez overland to Alexandria with a three-day stop in Cairo. During his short stay, Tao visited The Great Pyramids at Giza and seemed to have even gone to the Luxor.[103] While these sites captivated Tao, his pivotal experience lay ahead of him.

Upon arriving in London, Tao seems made a bit of a sensation. Everywhere he went, curious Britons approached Tao and openly conversed with him on a variety of topics.[104] Moreover, his liberal temperament made him all the more approachable and was willing to learn about the West from anyone who would teach him. In particular, Tao enjoyed visits to the Crystal Palace where all sorts of curiosities and inventions were on display. Also, during his time in London, Legge took Tao to the British Museum and he marvelled at its collections of various historical and natural wonders from across the globe. Shortly before leaving England, Tao was asked by Legge to give a lecture at Oxford. While Tao moderated his tone, perhaps out of respect to Legge, he did touch upon the idea of cross-cultural exchange and the “Way of Great Unity,” [105] which would become one of favourite topics later in his life. The muted lecture was well received, and the assembly hall shook with a favourable applause.[106]

In his travel writings, Tao would spend quite a few pages describing the sights and intricacies of Britain, right down to the cast-iron water pipes.[107] The significance of this period in observed in the fact that, during the two years Tao spent in Britain, Legge would take Tao on short trips across Britain to see what Western civilisation had to offer. Tao seems to have seen almost everything the West had to offer; he visited munitions factories, military training exercises, coalmines, museums, paper mills, hospitals, and universities. With each new experience, Tao allowed himself to be saturated by it. These experiences were arranged for Tao at the behest of James Legge, through his numerous contacts. Similarly, Legge became Tao’s access point to the innovations that Western civilisation had to offer. Though, Wang Tao’s experiences in Britain did not completely change his conception of the West what it had to offer China. It did contribute to the solidification of concepts and arguments that he had been reflecting on since the late 1850s.

Historian Paul Cohen accurately compares Tao’s explorations to that of a graduate student, who completes his training by spending a few years in the field.[108] Accordingly, Tao’s time in Europe provided him with a real feel of the limitations and realities of Western life and culture. Other Chinese would not have Tao’s opportunities until the mid-1870s and 1880. While other Chinese scholars were advocating for Western reform in China, only Tao had experienced these things in person. The important result of this European excursion for Tao would be to solidify within him the notions that would drive him to pursue a lifelong career a lifelong career advocating for Western-style reforms within China. Ultimately, James Legge facilitated this mental shift in Tao by demonstrating that he held a sincere appreciation of Chinese civilisation and by affording him the opportunity to have that cross-cultural exchange. Consequently, both men became access point from which each could explore and engage with the culture of the other. In doing so, they came to understand the other’s culture and recognised the benefits of their intercultural intercourse.

Conclusion

It takes a distinct arrangement of historical and biographical conditions to enable an individual to break with conventional cultural norms and to chart new cultural conduits. Historically, China in the latter half of the nineteenth-century was at a significant juncture in its development. Inundated with innumerable difficulties and threatened with unparalleled challenges, the opportunities for necessary change were present as they had never been before. In the turbulent environment, Wang Tao emerges as a new type of Chinese citizen. The subsequent life crises Tao faced – his failure to pass the Imperial examinations, the unexpected death of family members, and the charge of treason – were all incidences that could have occurred in any period. But, the means by which Tao extricated himself from these unfortunate events were only available during this critical clash between China and the West in the latter half of the nineteenth-century. Accordingly, Tao was living in an era of fundamental transformation within Chinese society. Similarly, the opening of China presented opportunities for European’s like James Legge that had previously been limited by the Qing Dynasty. Through the contentious and violent events of this period, both Tao and Legge would be forced to confront the consequences of the sustained contact between their civilisations. These events of served to alter their perceptions of one another’s culture and enabled them to make the mental shift that their contemporaries were unable to perform.

Nonetheless, such changes in one’s worldview are usually a gradual process, and that was the case with both of these men. James Legge shift would occur as an outgrowth from his regret over British imperialistic policies that wrought such death and destruction on China. Legge was also deeply affected by personal contacts with Chinese scholars, such as Hong Rengan. The combination of these factors helped shape Legge’s beliefs and laid the groundwork for the shift that Wang Tao would later facilitate. Tao enabled Legge’s mental pivot (or as Girardot terms it, Legge’s hyphenation) by becoming the filter from which Legge distilled classical texts of Chinese literature. Tao accomplished this by compiling extensive commentaries on the texts that Legge was translating. Legge then used these commentaries to explain the meaning the texts, which is evident in the footnotes of these works and by Legge’s own admission. Such was Tao’s influence and that Legge later admitted that he could not find another Chinese scholar to compare to Tao.

Comparably, James Legge had a profound effect on the mental shift of Wang Tao. The key ingredient in Tao’s mental pivot was his exposure to the West, gained through personal contacts and by traveling to Europe. The missionaries Tao was exposed to were not common run preachers. Rather, these men were the scholar-elite of the Protestant mission in China. Both Legge and Edkins were men, had openly demonstrated a genuine appreciation of Chinese civilisation and that it was worthy of academic study. These experiences were arranged for Tao at the behest of James Legge, through his numerous contacts. However, the most significant contribution to Wang Tao’s shift was Legge’s invitation to join him in Scotland at the end of 1867. While in Europe, Legge became Tao’s access point to the many of the innovations that Western civilisation had to offer. Though, Wang Tao’s experiences in Britain did not completely change his conception of what the West had to offer China. It did contribute to the solidification of the concepts and arguments that he had been reflecting on since the late 1850s.

Together they began a process of cross-cultural exchanges that we are still in the midst of today. Though from different backgrounds and societies, the two men had a similar shift in how they thought about one another’s society. This modification of thought made it possible for both men to appreciate each other’s civilisation and to attempt to understand it through intimate contact with the opposite. Though lost in the haze of the vastness of human history, the story of Wang Tao and James Legge is compelling because it demonstrates that, through forthright engagement, we can overcome the predispositions inherent within the human condition. Ultimately, that is their legacy and example that they provide for future generations.

As a final point, it is important to note is that this paper in not an exhaustive study of the relationship between Wang Tao and James Legge. Nor does the paper explore the implications of their cross-cultural exchange in any great detail. This paper is only indented to be a starting point, where other intrepid seekers of knowledge may pick up the scholarship and expand upon this remarkable story. Appropriately, there are areas for further research. The next phase in the development of this thesis would be for the keen scholar to comb through Wang Tao’s paper for references to this eleven-year association with James Legge. Furthermore, a thorough examination of Tao’s commentaries would also be prudent because these were the texts that Legge used to inform his translations and opinions. Such a resource would be invaluable when attempting to discover what concepts Tao was filtering to Legge and how is that reflected in his translations. In addition, the papers of James Legge should also be re-examined for references to Wang Tao. Both men left a decent number of letters and other documents, which ensures that more evidence to support this argument is merely lying in wait.

Bibliography

Anderson, Gerald H. Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 1998.

Cohen, Paul A. Between Tradition and Modernity: Wang Tao and Reform in Late Ch’ing China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1974.

“Huang Wan K’ao.” In Chinese Communist Studies of Modern Chinese History, compiled by Albert Feuerwerker, translated by S. Cheng, 136-39. Harvard East Asian Monographs. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961.

Girardot, N. J. The Victorian Translation of China: James Legge’s Oriental Pilgrimage. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

Hall, Edith. Inventing the Barbarian: Greek Self-definition through Tragedy. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991.

Hanes, William Travis, and Frank Sanello. Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2002.

Legge, Helen Edith. James Legge, Missionary and Scholar. London: Religious Tract Society, 1905.

Mao, Haijian, and Julia Lovell. The Qing Empire and the Opium War: The Collapse of the Heavenly Dynasty. Translated by Joseph Lawson, Peter Lavelle, and Craig Smith. 1st ed. The Cambridge China Library. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

McAleavy, H. “Wan TaoThe Life and Writings of a Displaced Person.” Edited by S. Howard Hansford. The China Society London, no. 7 (1953): 1-40.

Platt, Stephen R. Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom: China, the West, and the Epic Story of the Taiping Civil War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012.

Reilly, Thomas H. The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom: Rebellion and the Blasphemy of Empire. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2004.

Smith, Richard J. The Qing Dynasty and Traditional Chinese Culture. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2015.

Teng, Ssu-yü. Historiography of the Taiping Rebellion. Cambridge, MA: East Asian Research Center, Harvard University; Distributed by Harvard University Press, 1962.

Tsui, Wai. “A Study of Wang Tao’s (1828-1897) Manyou Suilu and Fusang Yuji with Reference to Late Qing Chinese Foregin Travels.” Edinburgh Research Archive. March 2010. Accessed October 23, 2016. https://www.era.lib.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/5620.

Waley, Arthur David. The Opium War Through Chinese Eyes. 1st ed. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1958.

[1] N. J. Girardot, The Victorian Translation of China: James Legge’s Oriental Pilgrimage. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 7-8.

[2] Gerald H. Anderson, Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions. (New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 1998), 393.

[3] Girardot, The Victorian Translation of China, 18-26.

[4] Girardot, The Victorian Translation of China, 31.

[5] Girardot, The Victorian Translation of China, 26.

[6] Legge, James, preface to the Rambles of the Emperor Ching Tih, v.

[7] Helen Edith Legge, James Legge, Missionary and Scholar. (London: Religious Tract Society, 1905), 129-30.

[8] Girardot, The Victorian Translation of China, 74.

[9] Girardot, The Victorian Translation of China, 63-66.

[10] Girardot, The Victorian Translation of China, 123-182.

[11] Girardot, The Victorian Translation of China, 513.

[12] Paul A. Cohen, Between Tradition and Modernity: Wang Tao and Reform in Late Ch’ing China. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1974), 9.

[13] Cohen, Between Tradition and Modernity, 10.

[14] Cohen, Between Tradition and Modernity, 12.

[15] Cohen, Between Tradition and Modernity, 13.

[16] Cohen, Between Tradition and Modernity, 13.

[17] Cohen, Between Tradition and Modernity, 13.

[18] Cohen, Between Tradition and Modernity, 19-23.

[19] Cohen, Between Tradition and Modernity, 21.

[20] H. McAleavy, “Wan TaoThe Life and Writings of a Displaced Person.” Edited by S. Howard Hansford. The China Society London, no. 7 (1953): 1-40.

[21] Cohen, Between Tradition and Modernity, 39-47.

[22] Cohen, Between Tradition and Modernity, 39-47.

[23] Cohen, Between Tradition and Modernity, 47.

[24] Cohen, Between Tradition and Modernity, 57-73.

[25] Cohen, Between Tradition and Modernity, 76.

[26] Cohen, Between Tradition and Modernity, 143-235.

[27] Haijian Mao, and Julia Lovell. The Qing Empire and the Opium War: The Collapse of the Heavenly Dynasty. Translated by Joseph Lawson, Peter Lavelle, and Craig Smith. 1st ed. (The Cambridge China Library. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 1-26.

[28] Mao, and Lovell, The Qing Empire and the Opium War, 74-129.

[29] Mao, and Lovell, The Qing Empire and the Opium War, 214-270.

[30] Mao, and Lovell, The Qing Empire and the Opium War, 271-341.

[31] Mao, and Lovell, The Qing Empire and the Opium War, 405-439.

[32] Mao, and Lovell, The Qing Empire and the Opium War, 433, 445-455.

[33] Richard J. Smith, The Qing Dynasty and Traditional Chinese Culture. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2015), 207-232.